How we see the world begins with the biology of sight. Most people have binocular vision, where each eye sends information to the brain to aid in perceiving 3D objects, speed of moving objects and depth. This stereoptic ability is not present at birth and begins around the 7th month and takes several years to perfect. Our eyes are not just lightbulbs that switch on at birth, we need to learn to see and that journey is important to understand.

The philosopher William Molyneux posed a thought experiment to John Locke, referred to in Locke’s, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding in 1689. ‘Molyneux‘s problem’ was a question about blindness :

Suppose a person born blind, and now adult, and taught by their touch to distinguish between a cube and a sphere of the same metal, and nighly of the same bigness, so as to tell, when they felt one and the other, which is the cube, which is the sphere. Suppose then the cube and the sphere placed on a table, and the blind person made to see: query, Whether by their sight, before they touched them, could they now distinguish and tell which is the sphere, which the cube?

Molyneux answered his problem and Locke agreed…

Not. For, though they have obtained the experience of how a globe, how a cube affects their touch, yet they have not yet obtained the experience, that what affects their touch so or so, must affect their sight so or so; or that a protuberant angle in the cube, that pressed their hand unequally, shall appear to their eye as it does in the cube.

In 2003, Professor Pawan Sinha at MIT was able to study 5 subjects that gained their sight after being born blind. They could not identify or recognize any shapes or objects. They don’t have a visual experience with a cube. Space, shape, length, and distance were incredibly difficult at first for each person to perceive. Seeing is embedded in experience as Locke responds in his essay…

This I have set down, and leave with my reader, as an occasion for us to consider how much we may be beholden to experience, improvement, and acquired notions, where we thinks we had not the least use of, or help from them.

This is a profound finding about how we comprehend the world and the physical and embodied necessity of experience. There is also the combinatorial complexity of sensory input that we use to not only move through this world, but to think through it as well.

We have prioritized an intellectual, literary, and linguistic approach to thinking and meaning making. The educationalist, Sir Ken Robinson quipped, “university professors… they live in their heads. They live up there, and slightly to one side. They’re disembodied, you know, in a kind of literal way. They look upon their body as a form of transport for their heads… It’s a way of getting their head to meetings.”

We prioritize our perception of reality, but what if that perception is wrong?

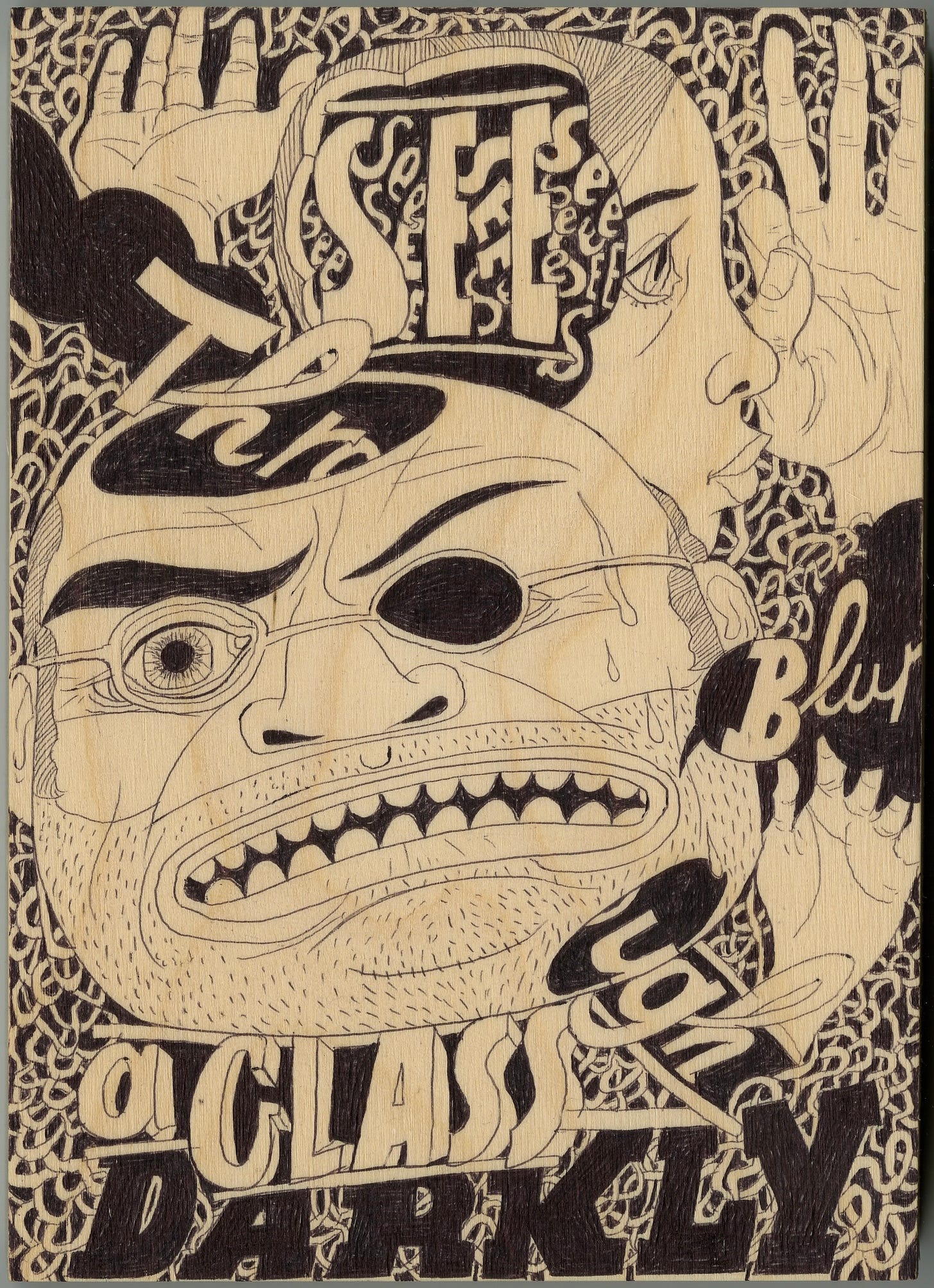

I am a member of the 4% of people that do not see the world in stereo. I am monocular and even with corrective lenses I struggled in high school playing some sports. I played baseball and was able to situate the high contrast ball in space…but basketball, the similar tonal value of the ball and the background made it difficult at first to read the ball’s location. But, I learned and my sense’s adapted my perception to train my brain. This experience with adapting visual phenomena, especially with each new prescription glasses, or visually taxing activity led me to understand seeing as not just looking, but as an engagement with my body through drawing.

Drawing combines memory with the hard work of recognition, or our lack of recognition when we have to draw a foreshortened form. Drawing provides an active engagement with form and interrogates the subject. It should be an embodied process of discovery rather than a technique driven visual vampirism that sucks the life out of subject matter in the hope that something meaningful survives. Like the academic painting re-enacters, the Bougeurocrats, trying to find meaning in reanimating a corpse.

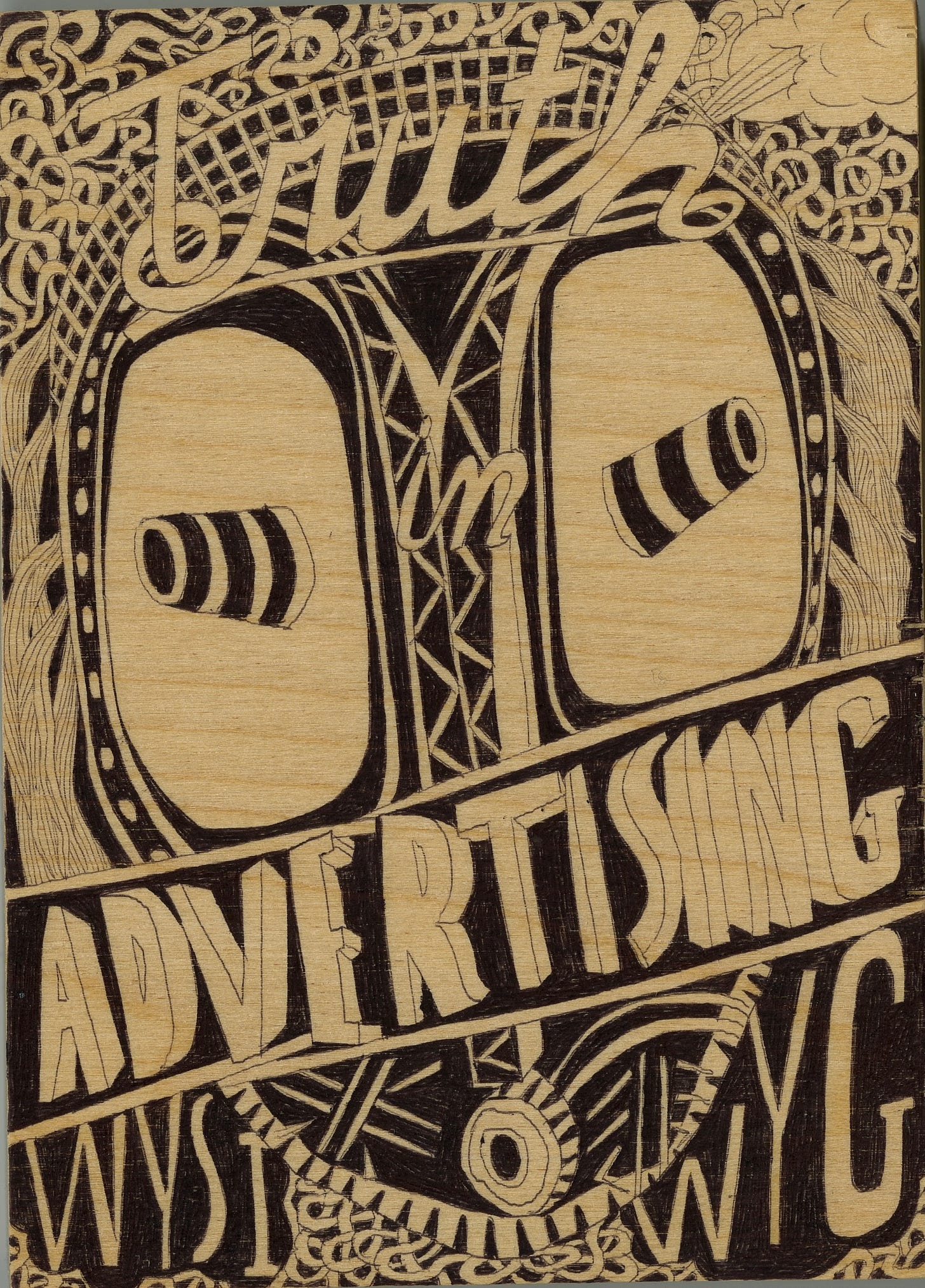

But I am getting ahead of myself as I am stepping out of the biological frame and stepping into the cultural and the polemical of next weeks Eyedrop and a dive into John Berger’s Ways of Seeing.