My research lab started again, the first week of studio courses. In a life drawing class the first thing we have to develop is a shared vocabulary. We aren’t agreeing on words that define the visual, words aren’t the determining lines of a colouring book and the visual the scribbled colours within the lines. Words are used as signposts to the visual, like a map of a city is actually different from living in it.

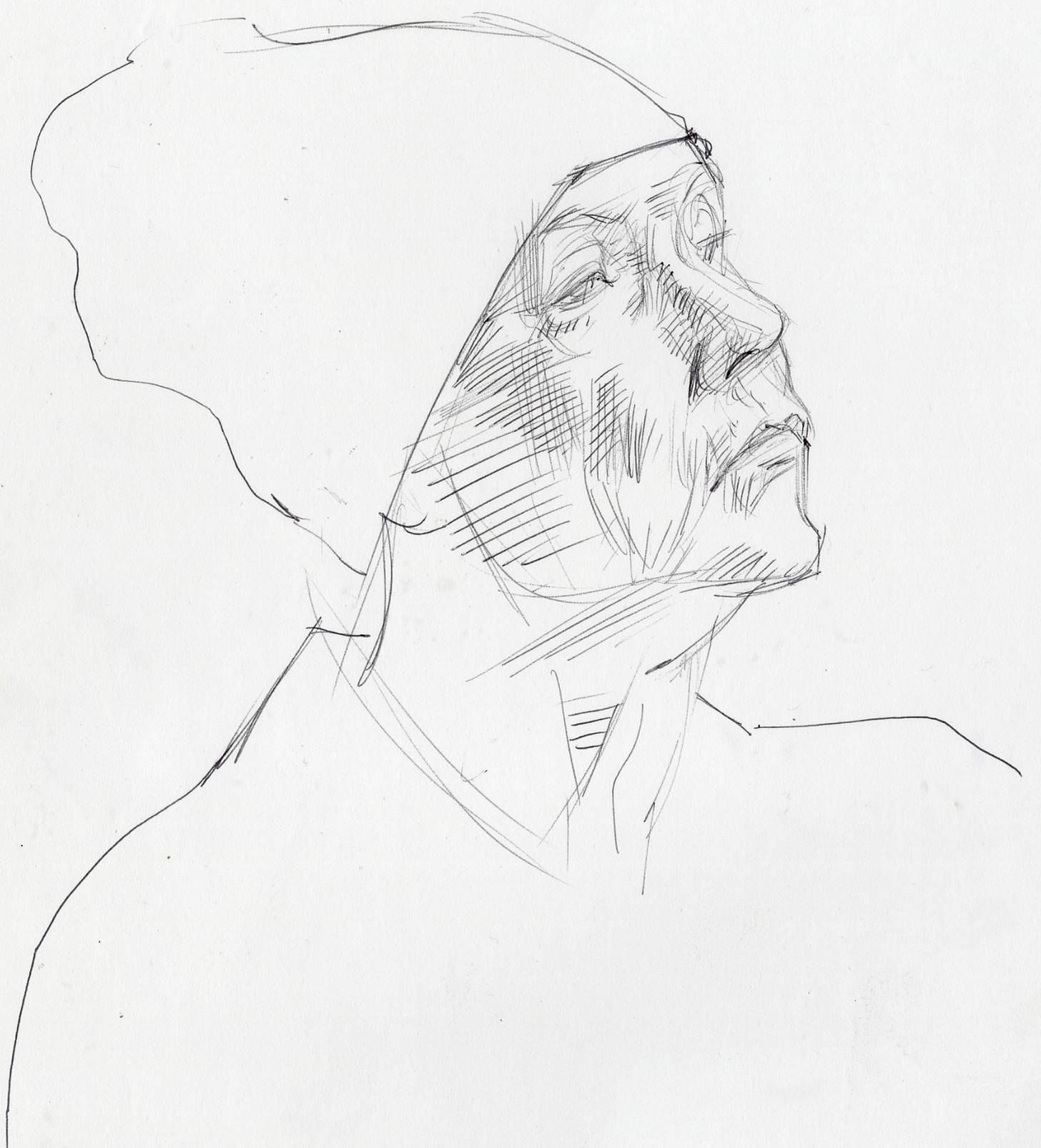

There is a wealth of information that each student expresses about the culture we live in as they draw a nude model on newsprint with a stick of compressed charcoal and clay. You can trace the education system, the art school concepts and the all pervasive social media water they have been swimming in. All of these prior experiences are profoundly visually literal. The language of the visual is almost completely alien to them.

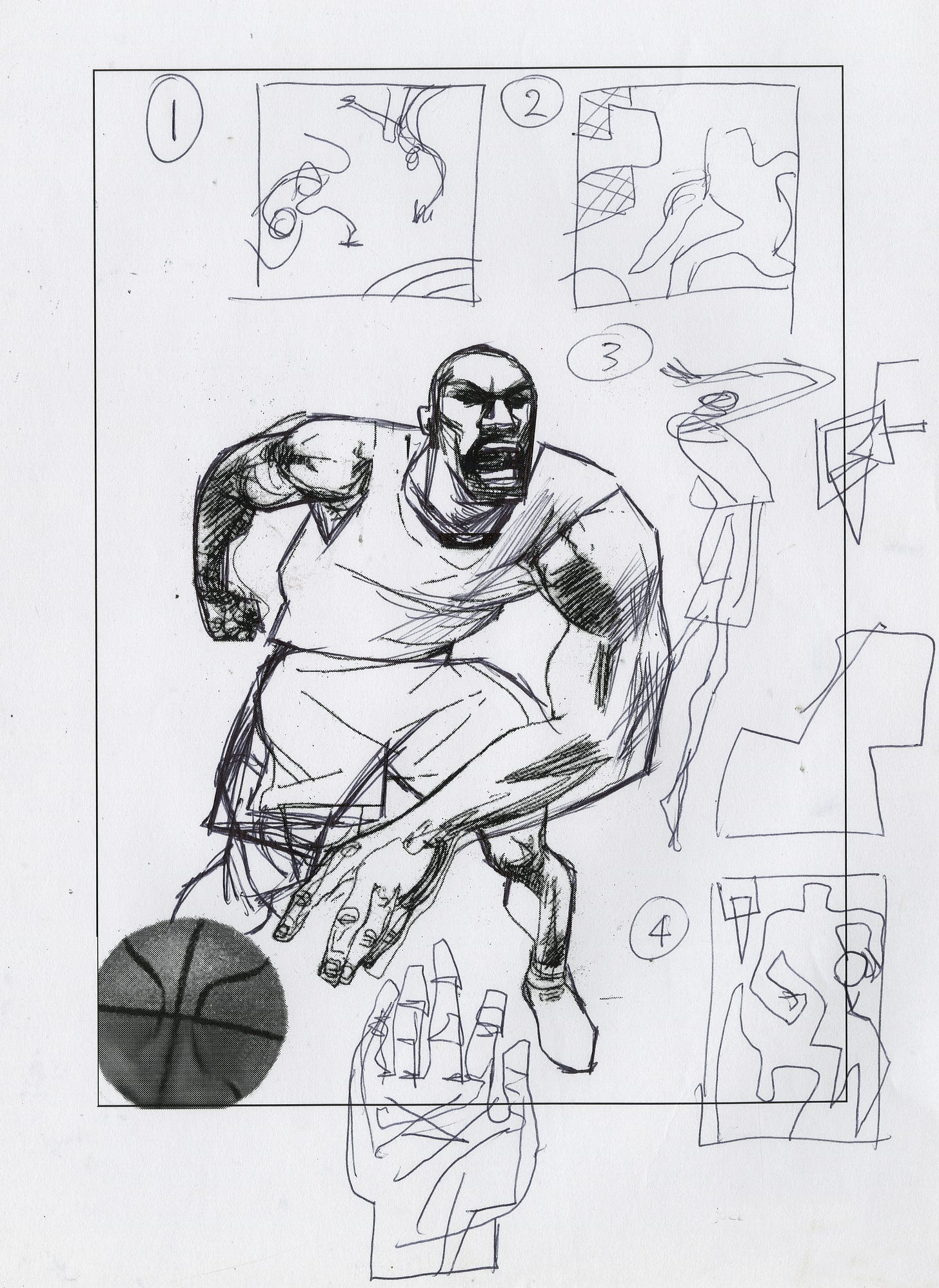

What is the language of the visual? It is not forged in words, but built by visual thinking informed by seeing and discerning visual truths. I went there, I used ‘truth’. Maybe my truth is closer to ‘truth in advertising’, which has the same dissonance as Car Park (thanks to UK graphic artist/illustrator Anthony Burrill, who has a way with pairing words), but just means draw what is actually happening. Drawing is a visual interpretation of the observed real or the unleashed imagination projected onto a flat piece of paper. No one is falling down a drawing of stairs, but that doesn’t mean those stairs couldn’t lead you somewhere. The real we contend with in life drawing class is informed by a person engaged with gravity and the very real space and presence at the heart of the experience.

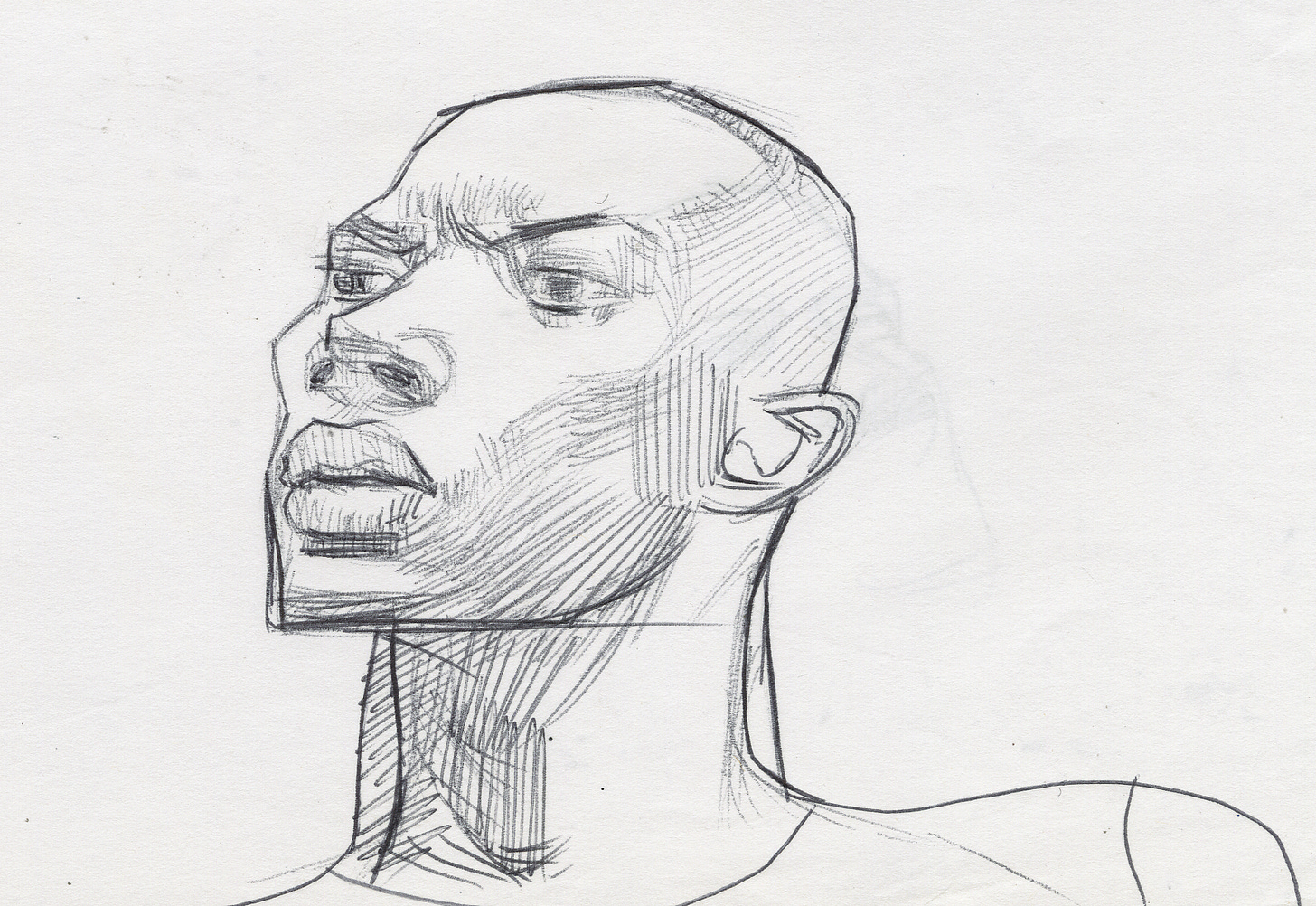

I’m trying to find the words that best express a process of seeing through bullshit, the omnipresent literal world that makes seeing so difficult and drawing so profound. I’m lucky to have had a front row seat for over 3 decades in the act of drawing. Watching how someone draws, it’s critical to see the first 15 seconds— where they start, how they look at the subject and their paper, the physical activity of their hand—-there is an incredible amount of information in those first marks on paper.

Mostly, novices draw the figure like someone who can’t swim thrown into a pool, with relief it is the shallow end and their initial panic subsides as they simulate some version of swimming. This makes perfect sense because in this world the literal is an ocean and the visual sinks or swims on its surface. Our own biology works against us in drawing as our senses are tuned for the tiger in the jungle and our eyes flit from one shiny thing to the next. Reading a pose does not come naturally and visual deception is hard wired into perception. This is not a recent observation—we can’t blame the internet for everything, this has been my experience for the 3 decades I have taught drawing. I also don’t want to confuse sociocultural effects with evolutionary change as the bold text below seems to suggest in an excerpt from The Medium is the Menace, by Andrey Mir. Our fingers aren’t changing shape because of texting.

When playing video games, digital immigrants instinctively dodge bullets or blows, but digital natives do not. Their bodies don't perceive an imaginary digital threat as a real one. Their sensorium has readjusted their bodies to ignore fake digital threats. There is no instinctive fear of heights or trauma in the digital world. Similarly, the fear of collision is cultivated by sports and physical activities, not by video games. In the digital world, even death can be overcome through re-spawning. What will happen when millions of young people with weakened grip strength, peripheral blindness, and no instinctive fear of collision start driving cars? Will media evolution be ready in time with its self-driving cars and self-driving everything?

The point of drawing for me is to be in control of how you respond to what you are seeing and the meaning you express. Visual people should be adept at navigating the constant static of visual content coming at them. There is no better place to do this than the life drawing studio. The human body is the single greatest visual subject we have because it is a form we have deep emotional attachments to as both a participant and a viewer. There is an energy in the drawing studio that springs from our need to connect and the community that drawing together creates.

The most difficult part of drawing is seeing what needs to be drawn and not what is most visible. Drawing as a skill has a ceiling that only thinking and meaning can break through, but the word world has other ideas about skills, as it offers techniques, tutorials, and exemplars of hard edged, and over drawn visuals. In some ways social media sells the same snake oil that the old Art Instruction Inc. ads in the pages of comic books sold—-Draw Me and display your talent. Talent is a terrible word, because it is both exclusionary and reductive. It’s another word that has no place in the drawing studio as we focus once more on the model and reach for our conté stick.