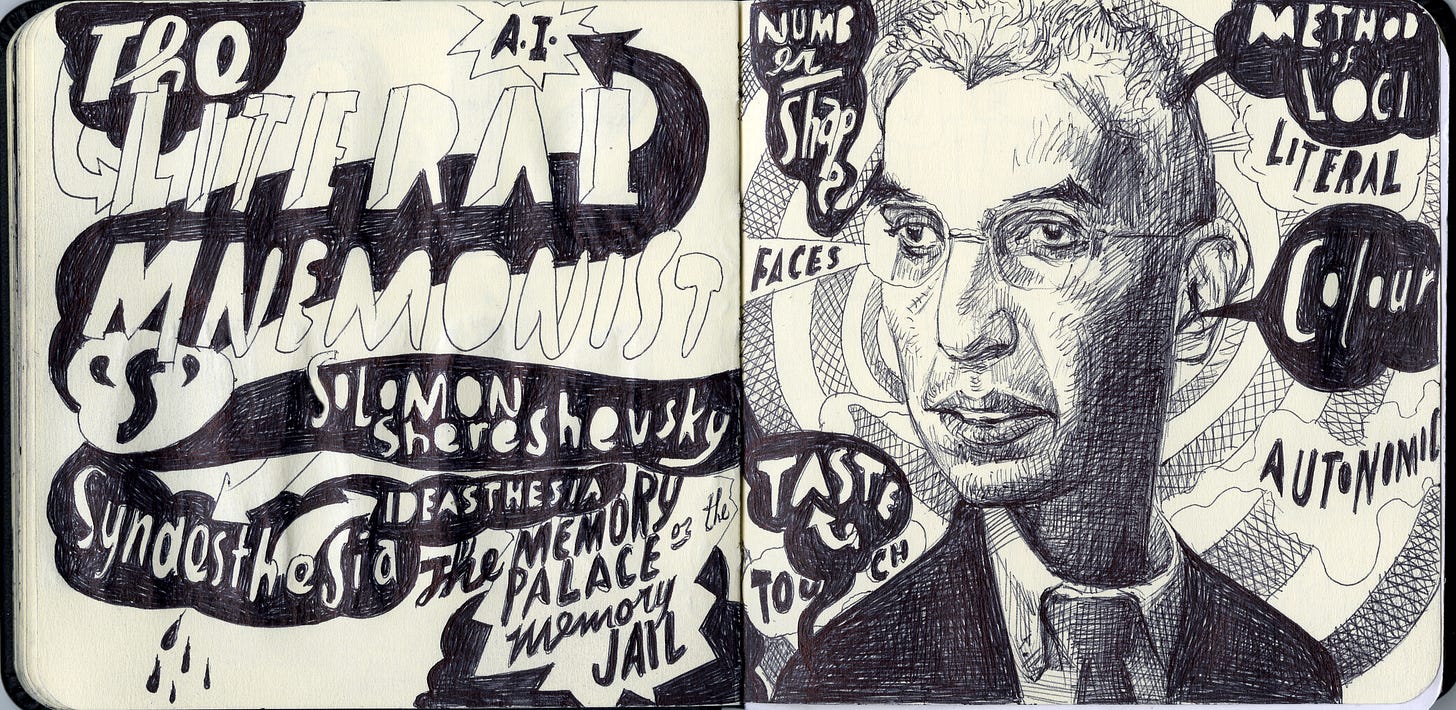

Superhero movies may be waning in popularity, but singular human stories like Oppenheimer still capture our imagination. In the 1920’s a Latvian journalist who never took notes because of his incredible memory became the subject, ‘S’ of the neuropsychologist Aleksander Luria. ‘S’ was Solomon Shereshevsky, and his detailed articles without notes, led his editor to send him to meet with Luria at the Moscow University. Shereshevsky was surprised that other people were unable to do this.

Luria presented him with complex scientific formulae, poetry in foreign languages, and long number matrices— he could memorize them in minutes. As his notoriety increased he became a fulltime mnemonist and extended his abilities into increasing and decreasing his pulse and even changing the temperature in his hands by imagining either ice or fire. Shereshevsky had an extreme form of synaesthesia where his senses were profoundly linked to his memory. Numbers were shapes, some words conjured colours or tastes. These various triggers helped him to remember everything, including the clothes Luria wore the first time they met.

But this was not a superpower but an anomaly and not an adaptation that made the world easier to navigate. First, he had trouble with people’s faces. He would memorize a face with a specific lighting, angle, expression, and age. Exactly the issue I have when working from photos to capture a portrait, the face radically changes depending on lighting, angle and age. Some photos don’t look like the person, so I understand his problem…the single snapshot in Shereshevsky’s memory was not enough. Abstract and figurative words were incomprehensible to him, his wife had to explain what ‘nothing’ meant. Fiction and poetry were opaque to him.

Solomon Shereshevsky’s super brain’s limitations should be a warning to us as we rely on digital super brains that may have even more catastrophic unintended consequences. Shereshevsky left the limelight and became a Moscow cab driver to escape the flood and crush of memory. The method of the memory palace, embedding information into a familiar place to aid in retrieval became a memory jail for Shereshevsky as forgetting became nearly impossible. The pictures we conjure to inspire our thoughts are cruelly leashed in his mind to the practical task of photocopying each distinct aspect of the everyday. As we venture down the path of releasing A.I. into our brain’s drinking water let’s not forget the panopticon prison of the man who remembered everything.