Sometimes the best way to learn something is to not do it. I don’t mean avoiding it, we are all too capable of doing that. I mean working on something else that can help you to better understand what you are missing. There are certainly no shortage of ideas, strategies and pro tips for creative problem solving, but I didn’t think I had a problem that I needed to creatively solve. I’m retracing steps rather than offering steps to take. See last weeks post on the reliance on method, as a well trod path to expertise that leads nowhere. A great example of confusing what it means to be an expert is this revelation from former race car driver Danica Patrick, “l’m just not a car girl.” She has no clue about engines and has no interest in how the car is built. “I can drive them.” Her shocked fans expected a gear head or atleast someone that cared about the vehicle, but she’s not an engineer or mechanic. Drawing comes with it’s own vehicle of practice and history that also misses the point of expertise or mastery.

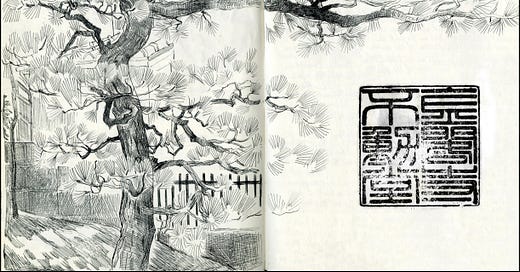

You need to bring more to the practice than just time spent and some bad historical ideas. Drawing the teahouses in Kyoto profoundly changed how I approached drawing the figure. This was neither conscious or intended, but the serendipity of an accordion fold book given to me as a gift and an extended stay outside of Kyoto that allowed me to visit for a number of days.

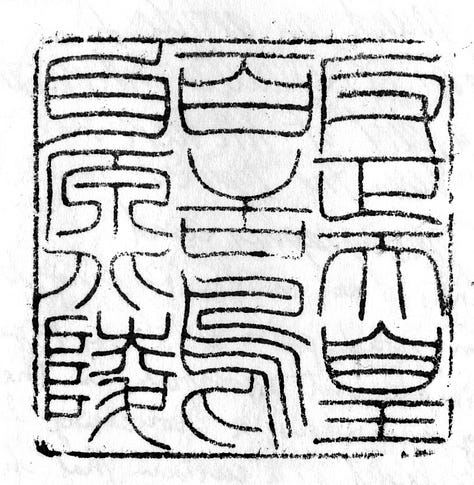

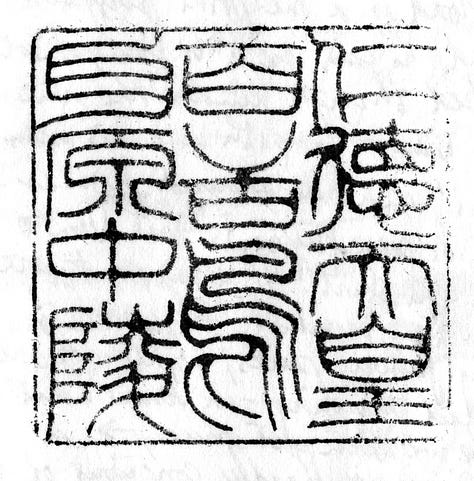

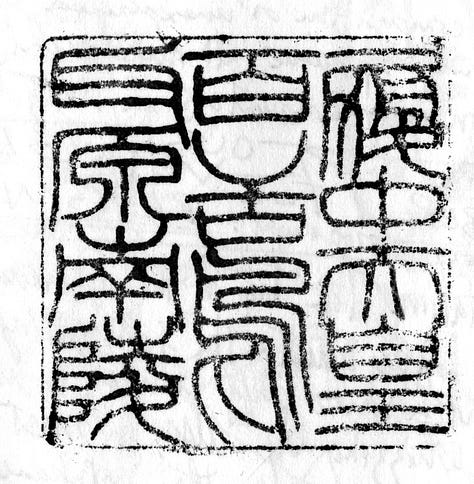

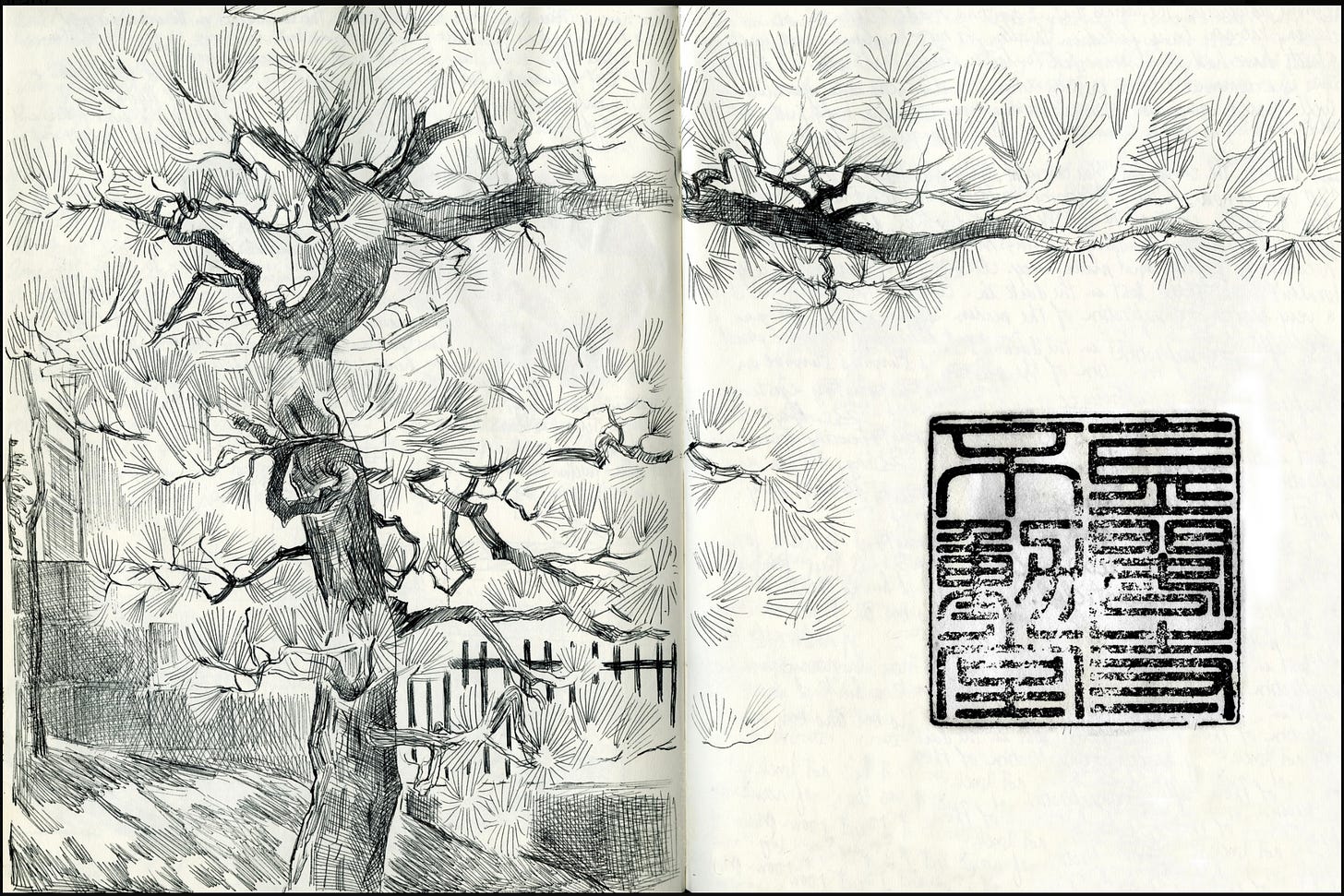

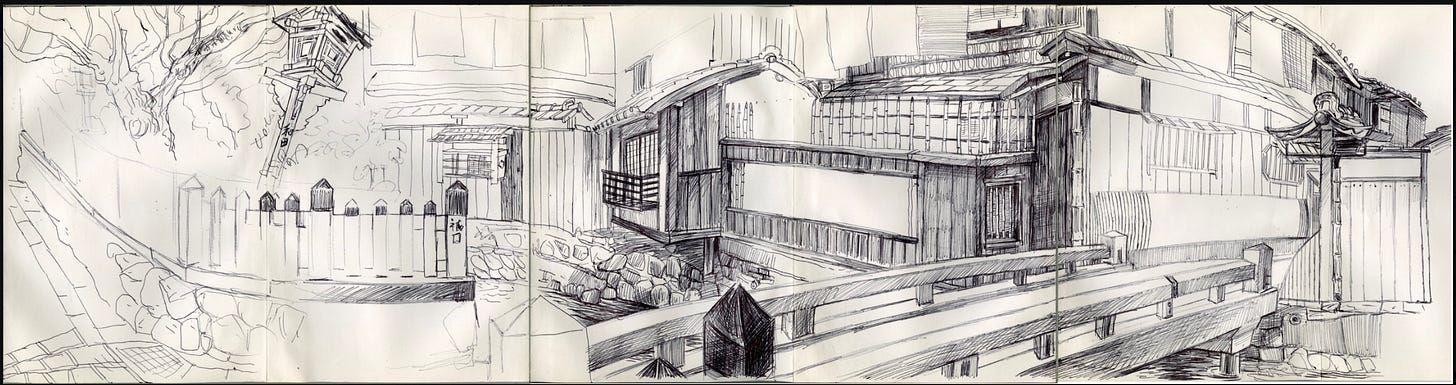

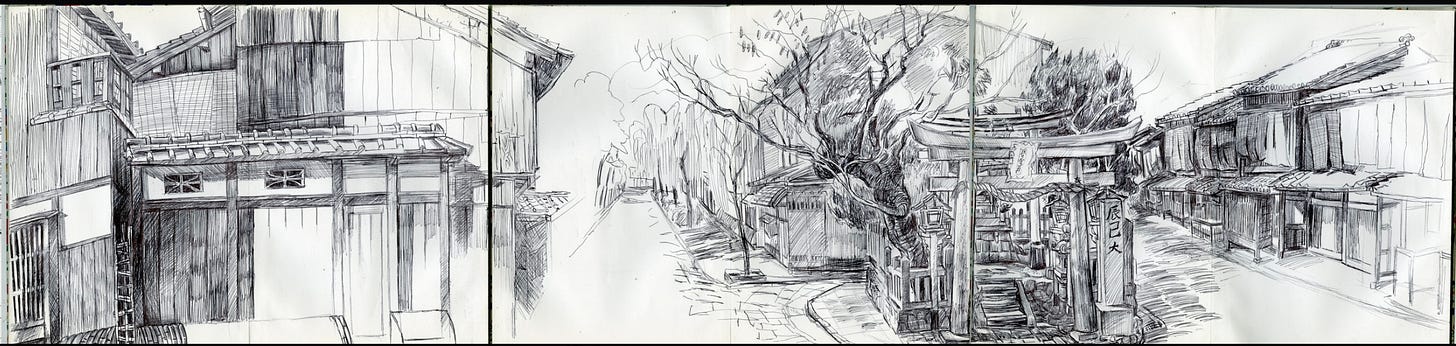

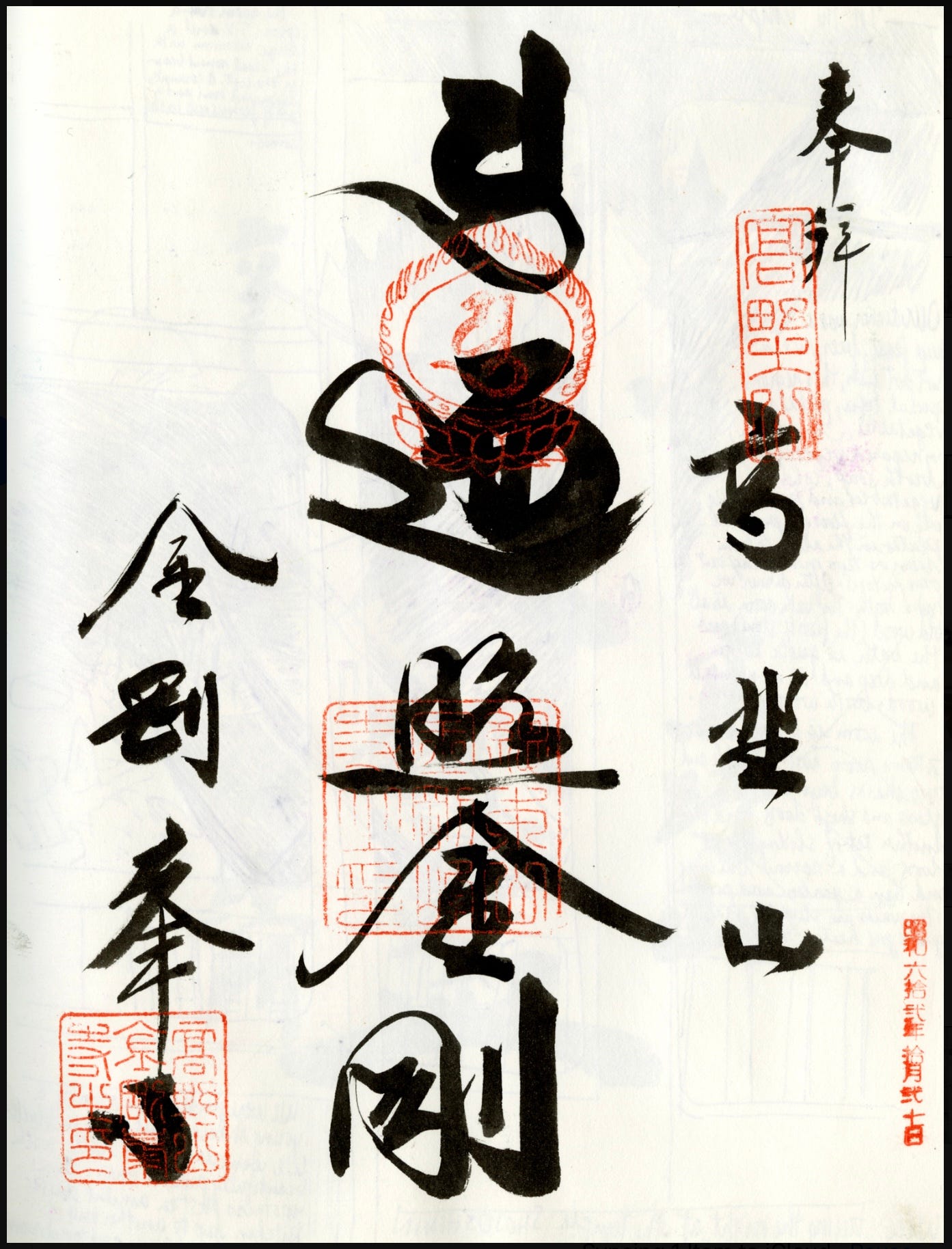

The first challenge of a six to eight page wide drawing is not seeing the entire picture at once as I’m drawing it. I drew on site and didn’t work on the drawings further, what I captured that day in that place was left ‘unfinished’. I had no idea that all of these constraints would offer me an approach to drawing that I would use for the rest of my life. Working in ballpoint pen, there was no going back and mistakes just became opportunities. The drawings are empty of people, I needed my subject to remain in place for the hours of observation it took to build this panorama of space.

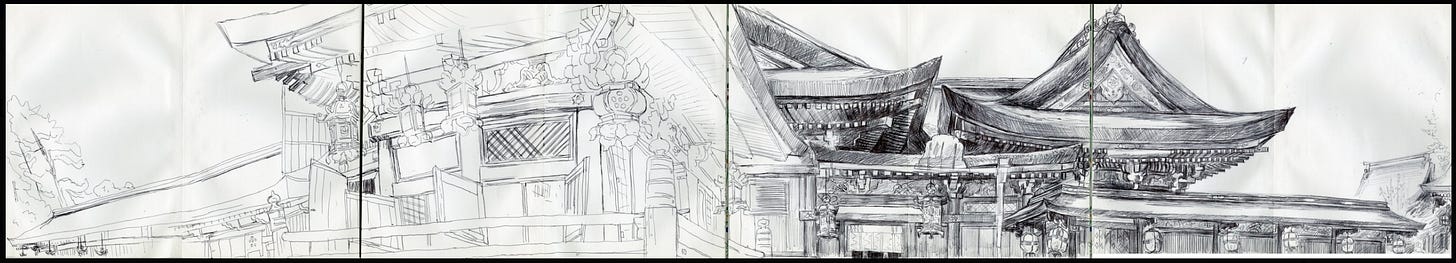

Everything in Japan was about space. The prevalence of earthquakes led to laws limiting the number of tall buildings in Japan (in recent years new technology has changed this) and the density of cities demanded that every space was precious. I stayed in family apartments in a tatami room with futons that would be packed away so that the room could be multi-functional. In Italy, I drew the characters in the Florentine piazzas as they sat on benches and cafes. In urban Japan it was constant motion and seas of people. From product packaging to rush hour on the Tokyo subway, space design/control was everything in Japan. The cultural influence of Buddhism and the Shinto religion on architecture was exemplified in Kyoto. This was the final mentor I needed.

The white space, the negative space, the space outside of the texture and pattern, needs to come to life in drawing. This is the most difficult thing to see because it is non-seeing, it is felt space or visual space that needs to be experienced. On these unwieldy pages—-these books are like Slinkys, those wire spooled toys that climb down stairs on their own—-if it slipped from your hand it would unfurl and cascade downward, I negotiated the order and the chaos of the subject onto the 2D surface of the book. The non-edge, or the continued horizontal space that I could continue to offerj into the drawing forced me to address scale and depth as a participant in the space. This for me is a key aspect of what these drawings taught me, engaging with the drawn surface as a space or field especially with observed subject matter. The result moves us physically and emotionally. I had no idea what the hell these drawings meant when I did them. In my journal at the time I had written this…

The quality we call beauty must always grow from the realities of life, our ancestors forced to live in dark rooms, presently came to discover the beauty in shadows, ultimately to guide shadows to beauty’s end. And so it has come to be that the beauty of a Japanese room depends on a variation of shadows, heavy shadows against light shadows…it has nothing else.

Jun’ichirō Tanizaki

Next week I’ll share how I brought this approach home to Toronto. It took another 4 years for me to make sense of this work as central to my figurative work. What we expect and look for may not be what we need.

“What we expect and look for may not be what we need.” Such an essential lesson I learned early but continue learn perpetually. Great series of writings Joe, eager for the next one