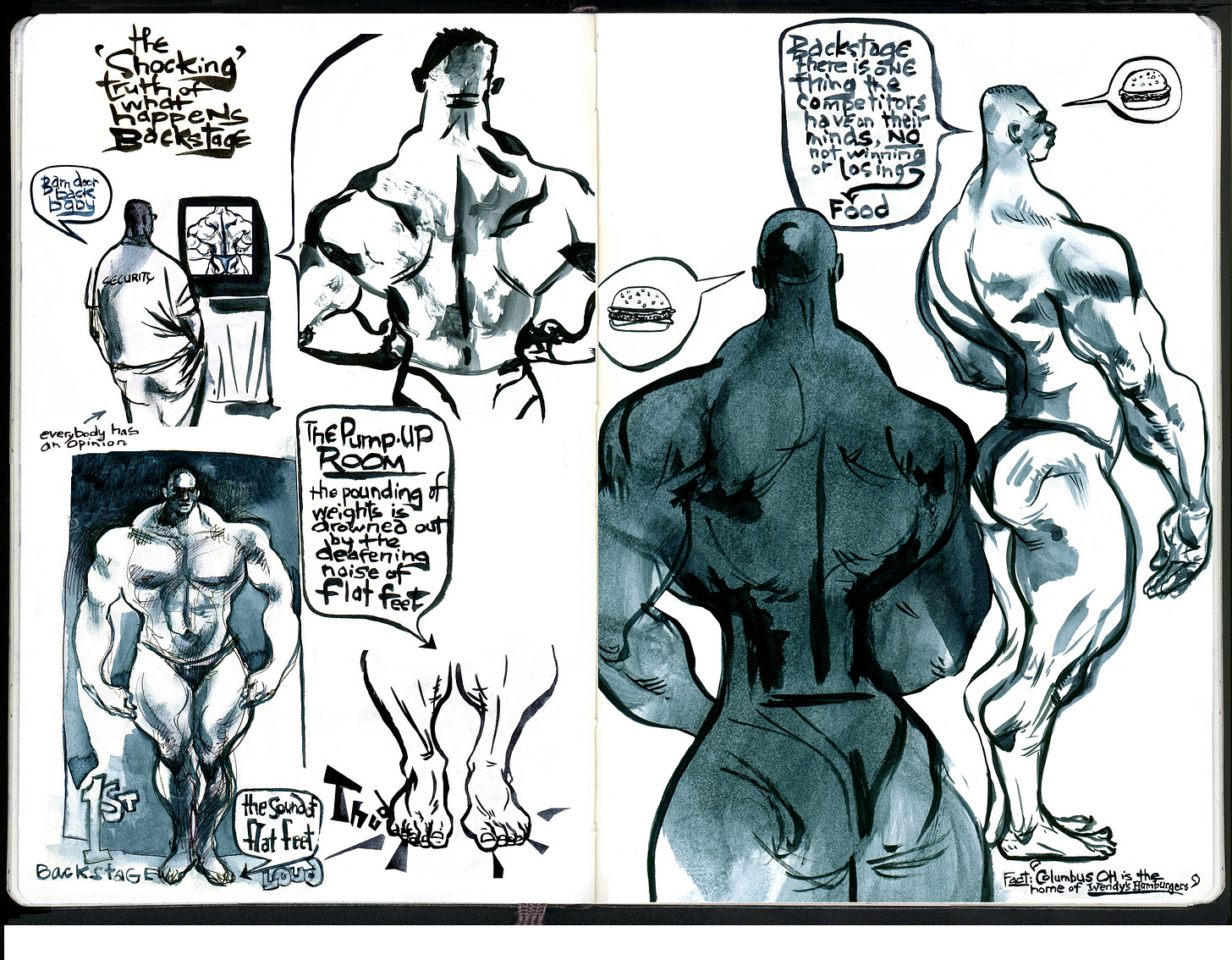

It’s week 2 in the life drawing studio and we battle the IKEA catalog we all carry in our brain. The familiar and habitual, the safe place we crawl into. Too many Illustration student crawls into this space tightly grasping their Apple Pencils. A life drawing studio is an interesting space, 22 to 23 introverts sitting/standing in a semicircle about to publicly scratch with a stick of compressed carbon black and kaolin, hopefully recognizable forms, onto large newsprint pads with a nude model and a timer. In my class, time is critical, especially when you start with a 15 second pose.

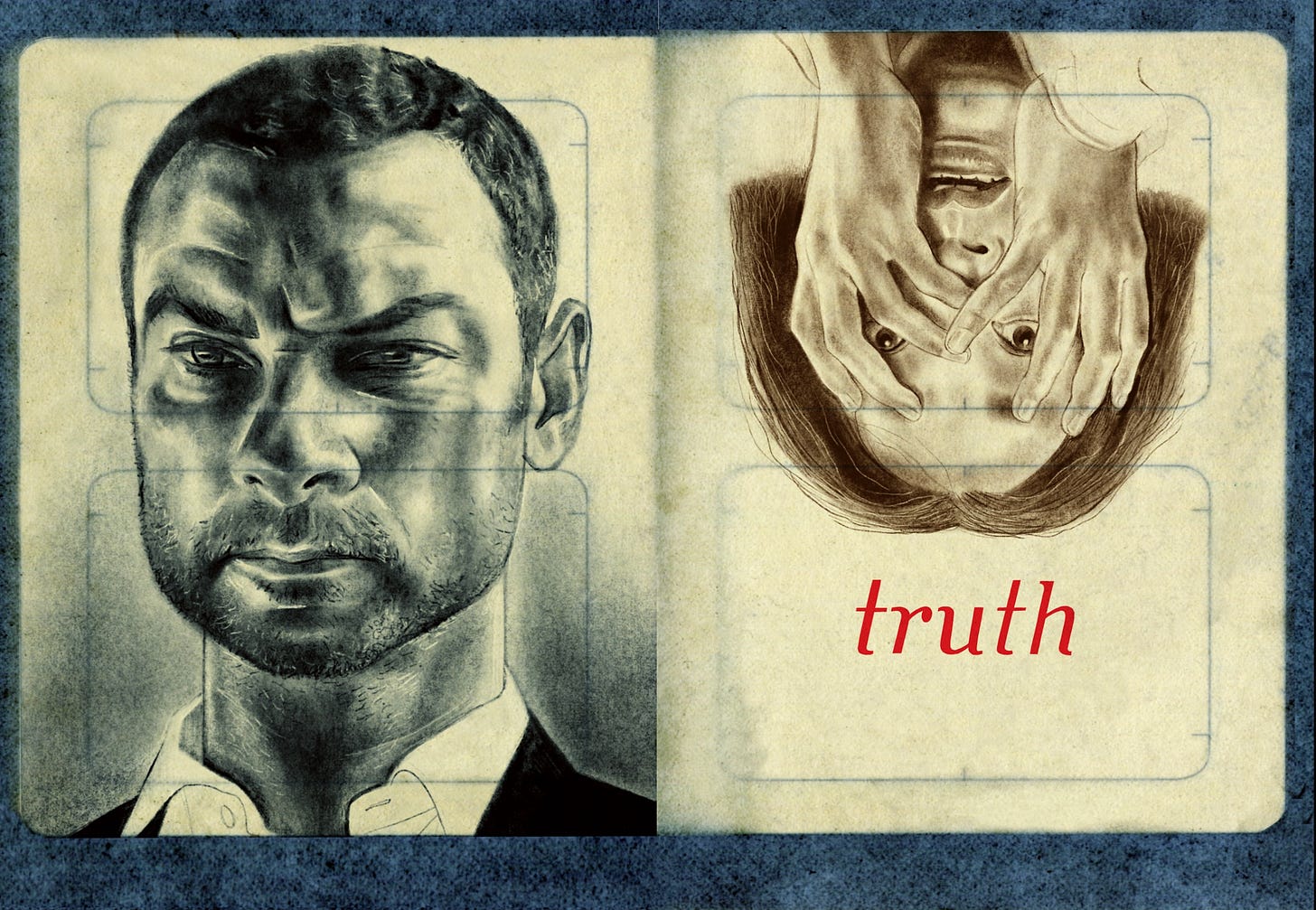

Teaching drawing begins by lying. The same kind of suspension of belief necessary to allow our imagination to conjure the stories and characters of fantasy—-because drawing is fiction. We are attempting to represent a 3D form on a 2D plane—it’s make believe, but we use the most tangible of forms; the cube, the cylinder and the sphere as building blocks, to tie ourselves back down to reality. These tangible models provide a way to see and draw 3D, but they are also mindtraps.

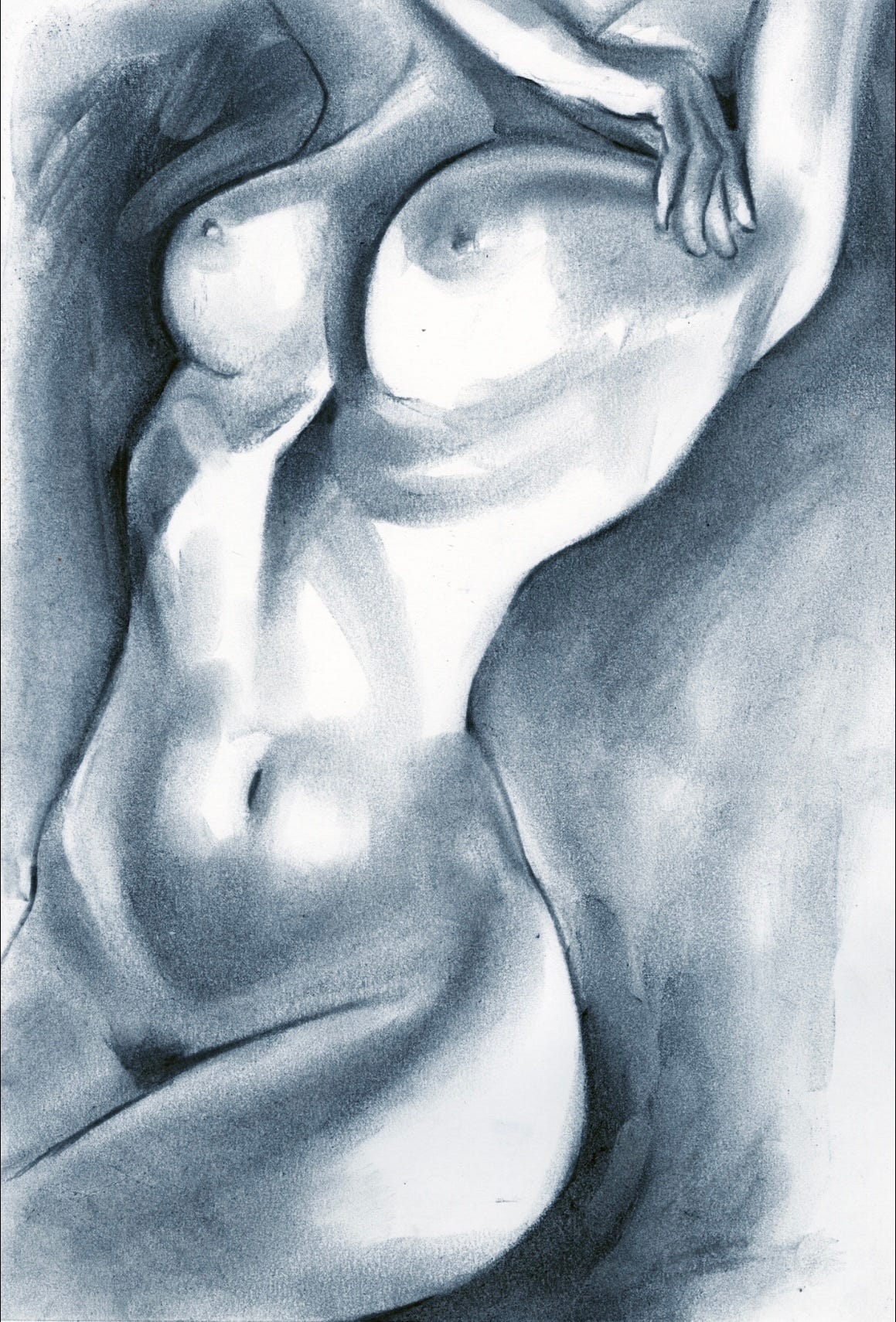

We need to cut the ties to the cubes, contours, and ovoids of learning to draw…the training wheels need to come off. But look online for all the building and structure methods to figure drawing——copy this character—-use this line smoothing app…none of the real problems central to drawing from observation need be bothered with.

But observation of life is the entire point. I am lucky, my marvelous students with their introductory drawing skills, habits, and years of anime drawing clutched in their arms are willing to try to shift the load they carry to another arm and try the exercises that I hope will slowly build an ember that will burn through the ties that bind their hands and heads.

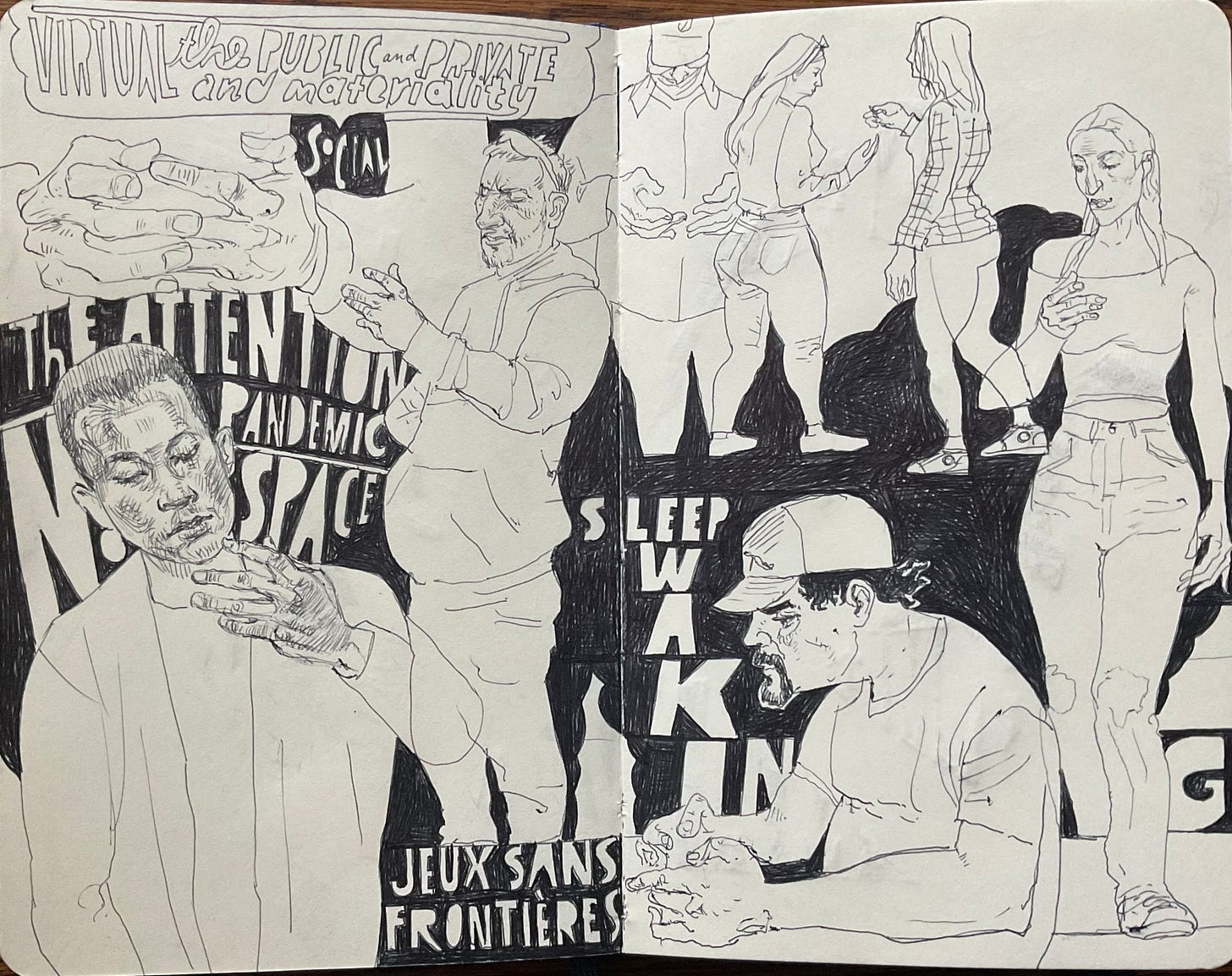

If teaching life drawing was only about teaching life drawing I would have stopped years ago. But arrayed across the studio are different people using lines on paper to express meaning and everything is written in those lines. The passive nature of our culture, the difficulty to be present, to be attentive, the constant problem with looking for meaning in all the wrong places.

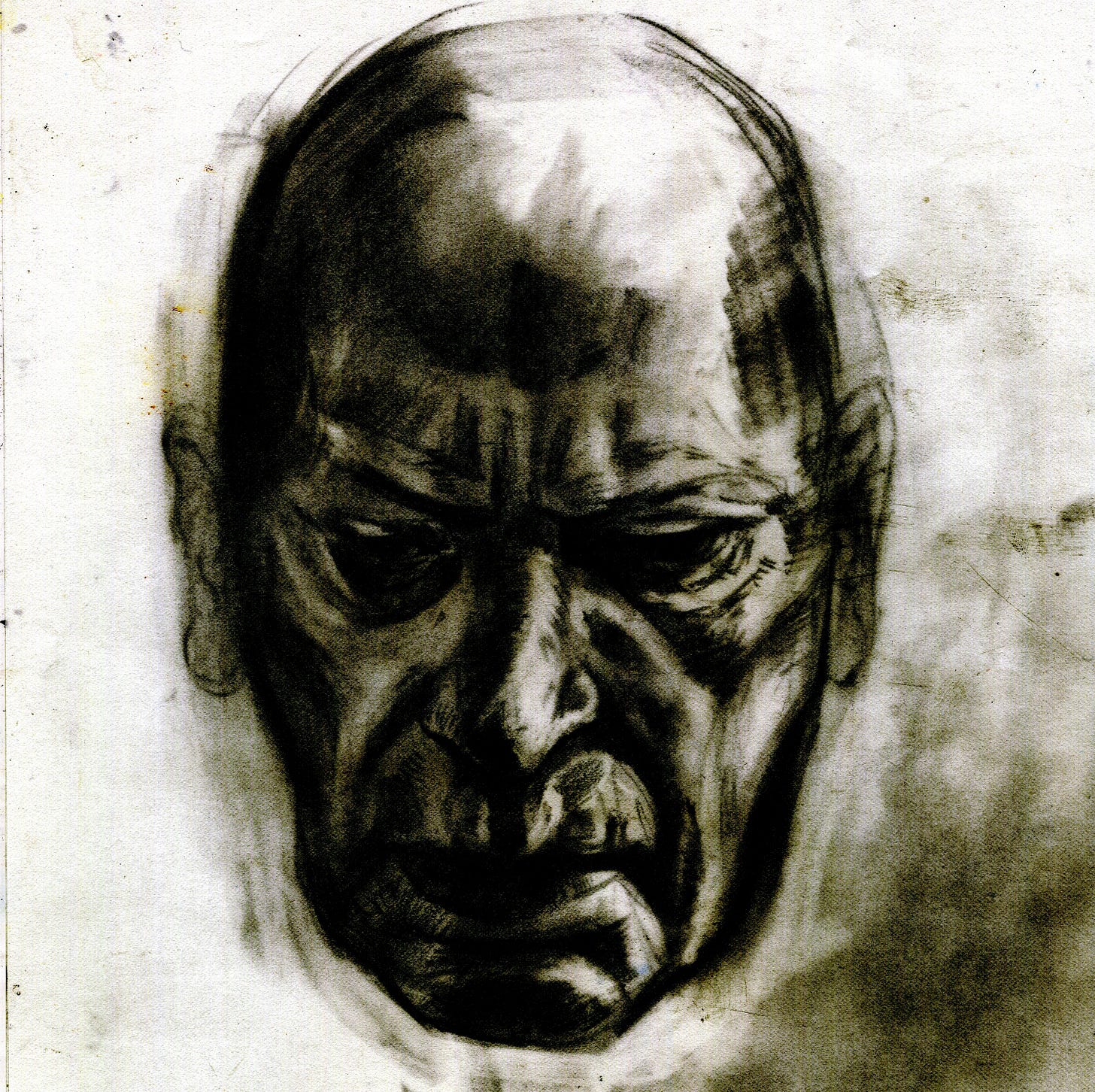

Our hardwired visual survival instinct obviously was successful or how would we be here today, but our damn eyes are useless for really looking. We like contrast, texture and detail, that’s why every novice draws the head first when it’s the last thing you should draw—-it basically just sits up there waiting for the rest of the body to tell it where to be. You don’t need to be an expert in anatomy to draw the figure, Da Vinci one of the first drawing anatomists saw the problem from the beginning—-when you know too much, you draw too much and you end up with a drawing that “looks like a bag of nuts.”

Changing how you see, finding a new perspective, making room for difference, moving outside of what you know, kind of seems like the point of learning and growing. We just try to do that with a nude model and 2 minute poses. So far so good, I’m 2 weeks in and the students are looking at me with less fear, because judgement isn’t the point—-there are no good or bad drawings —-it’s the questions you need to ask yourself that are terrifying.