It was a week of stupid, I made the mistake of delving into an X thread on A.I. and then the good old algo decided to drown me in A.I. posts, including Steven Heller taking ChatGPTimages for a spin—-not exactly sure why, a podcaster talking about ‘treating people like human beings’ with A.I. imagery front and centre, a takedown in Nature of a new book critical of digital technology by a professor whose work is directly funded by the edtech industry and some techno-futurist who thinks the world’s real problem is that we need a 100 billion interns (just guess what the fix for that is).

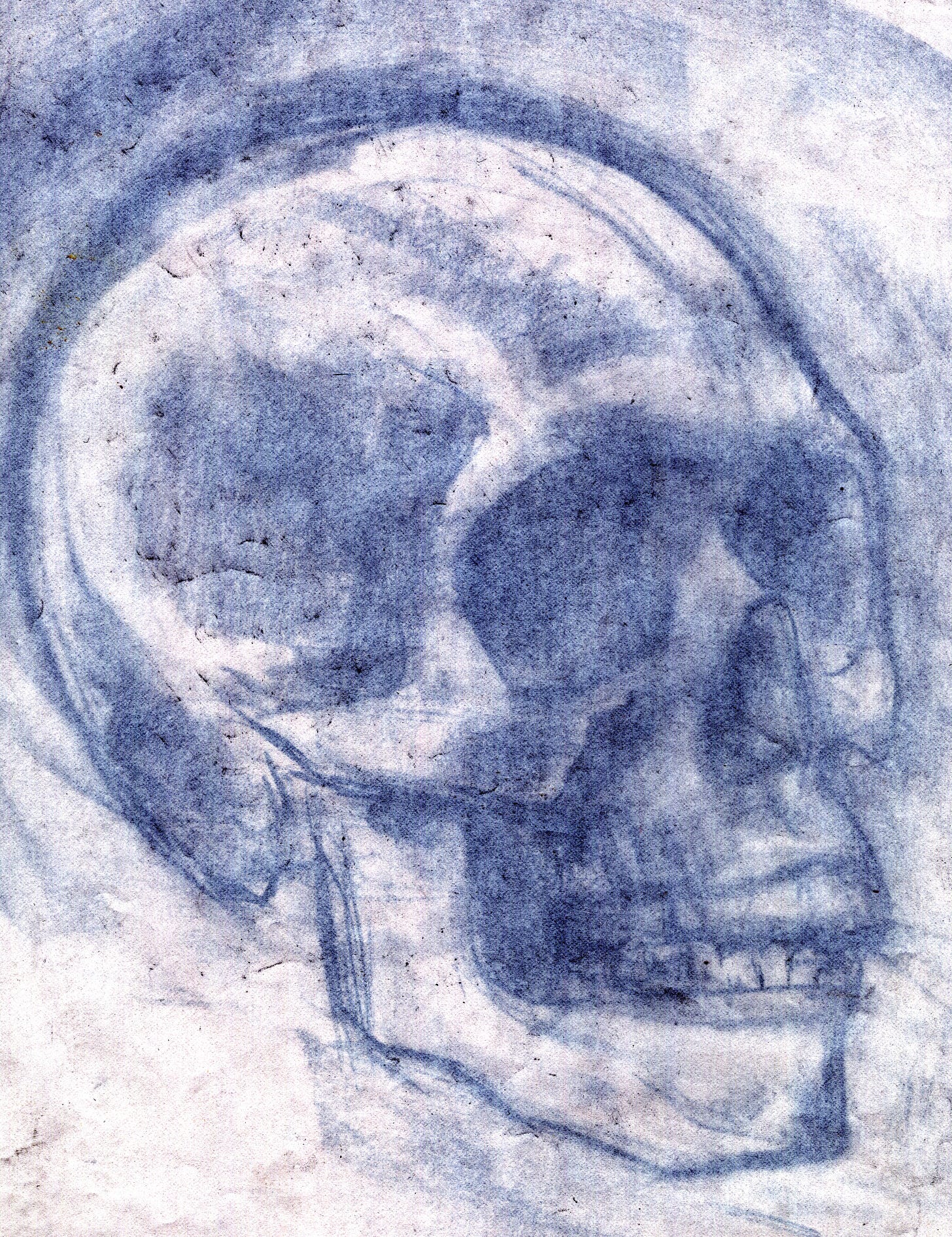

I needed some brain cleanse, so I dug more into the neuroscience of drawing. In 2019, Science Daily published a study from The Journal of Neuroscience (lead author Judith E. Fan) on how the brain sees drawing. Using fMRI and magneto encephalography the researchers saw the occipital cortex (visual processing) was active for both seeing and drawing, but the more drawings the subjects did the connection between the occipital cortex and parietal cortex (motor planning) grew—-the ‘muscle memory’ that comes with practice. Would love to see the effects of working from life vs screen and digital vs materials media.

Then the wonderful serendipity of not looking for something, led to finding something. Martin Hebart at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognition and Brain Science was trying to see how we read photos of objects vs. simple (very rudimentary) line drawings. All that added photographic detail would likely make recognition easier and faster. He found no difference whatsoever. But somehow this study was on a link page that mentioned Richard Feynman. I was first introduced to Feynman during the Challenger committee meetings—-well summarized in Edward R. Tufte’s book, Visual Explanations. Onward down the rabbit hole.

Feynman is the King of analogy and experimentation. If ever there was a model for the supremacy of human thinking over the machine, it’s Richard Feynman. When we look at the greatest discoveries and the greatest creative minds it isn’t genius, it’s as Feynman described science, “What way do we need to think about it so that we can understand it’s simplicity.”

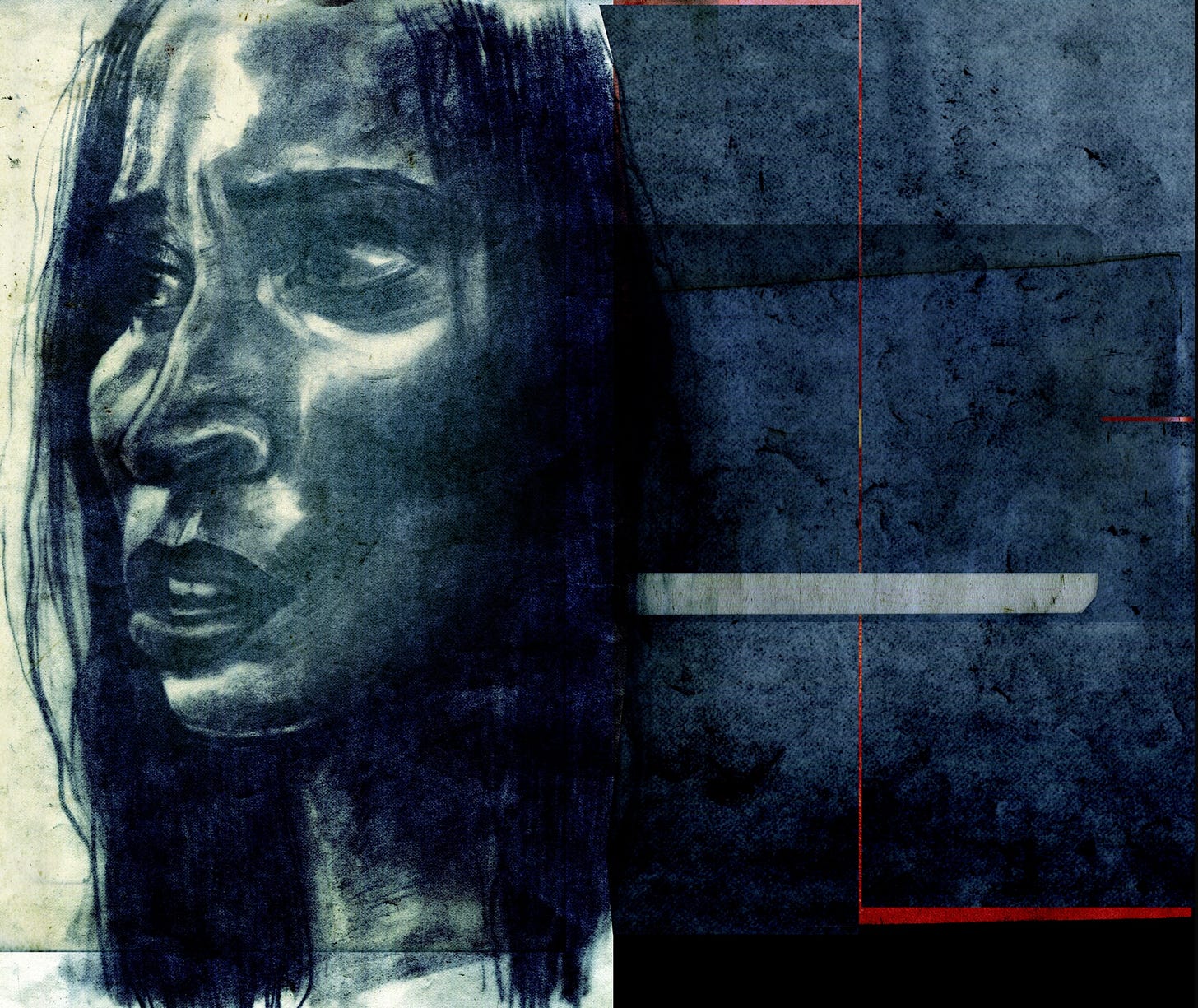

Simplicity. One of my favourite words in drawing. We either generalize (use some bad convention) or complexify (an even worse method —looking at you Reilly) when we are drawing form. Simplifying is designing the essential and finding your path between slavish copying and blind stylization. In the film Take the World From Another Point of View, Feynman is in conversation with the astronomer Sir Frederick Hoyle. Hoyle tells the ‘streetlight effect’ story.

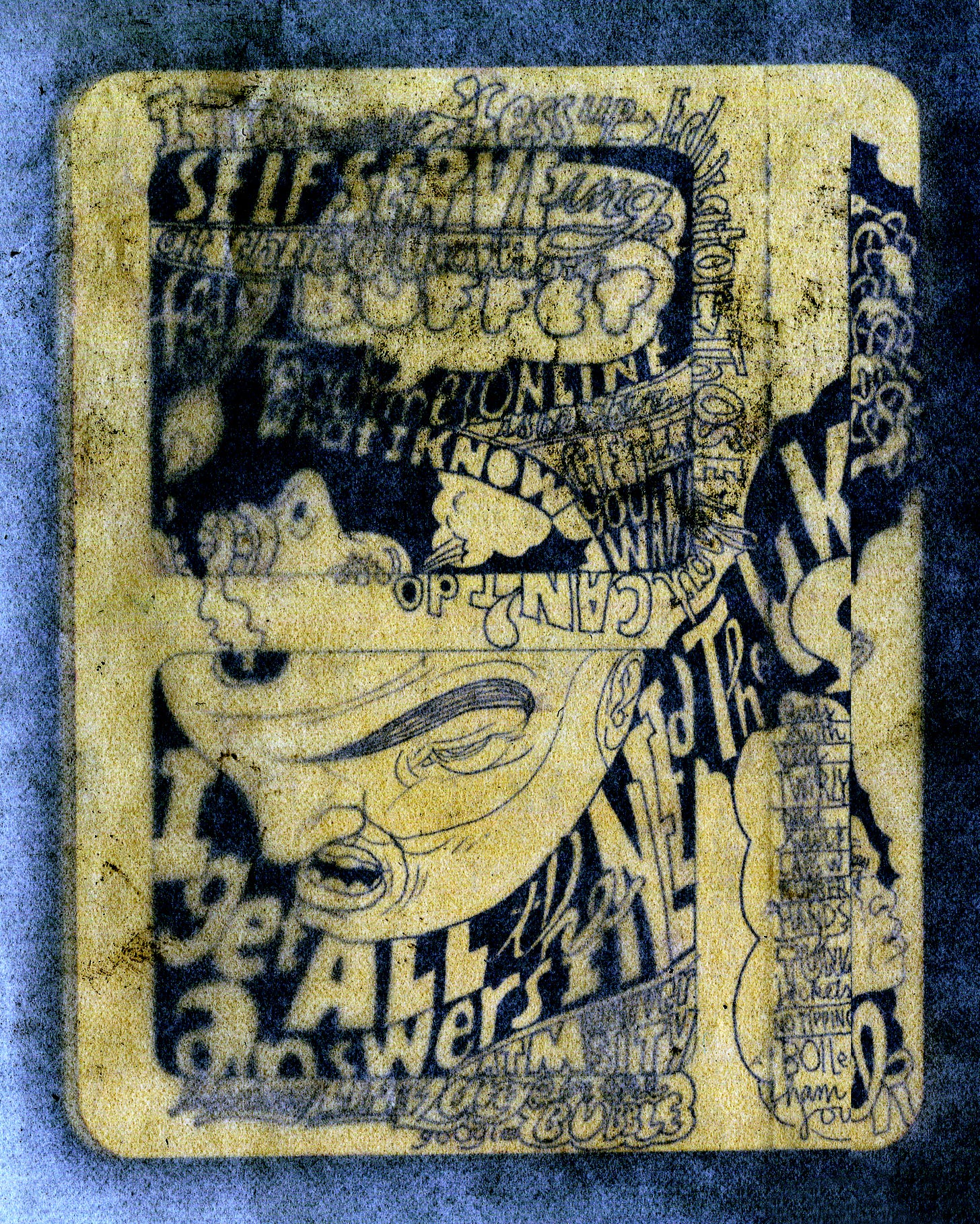

A man is searching for his keys under a street light at night. Another person comes to help him and as they both search asks, ‘are you sure you lost them here?’ The man replies, ‘not at all, but if I didn’t lose them here, I’ll never find them.”

Feynman laughs and adds, ‘We work where the light is better.’

If ever there was a metaphor for the core problem of A.I. as creativity, this is it. We are looking for answers in the glaring flood light that the LLM’s generate, but our answers, the keys to our problems lie in the dark outside that glowing pool. Feynman also describes in the film, the path of discovery and looking at something as if it is the first time. This is a profound idea that is so simple we ignore it. The real test is experiment, where history is futile as a guide forward, because all the methods we have tried in the past are not helping us to solve the problems infront of us.

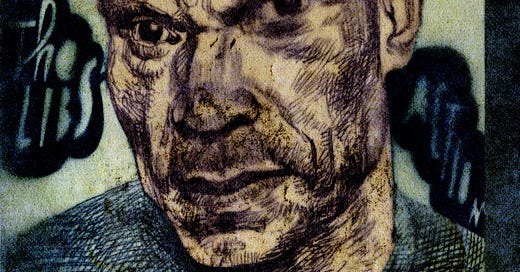

Feynman inspired me to return to the blackboard this week and my own love of analogy took over as I described the problem of drawing angled forms. We are terrible at guessing angles so we rely on our IKEA catalog of familiar forms in our heads. My favourite student approach is angling your head to attempt to straighten the subject to draw it, as if you were reading the text on a page in a book turned on a table, but we are not reading text we are seeing form in space. When a head is angled, typically the subject’s nose is closer to horizontal and the eye is closer to vertical, but your brain is screaming ANGLES—so that is what you draw—and the drawing falls apart. Looking at something like you never saw it before, seems like a good plan.