I was on the crowded Bloor subway train this week when I heard someone calling out short snippets of repetitive song. As the numbers of passengers dwindled I sat down facing a man and a teen boy, the source of the intermittent singing. He had a small Lego construction in his hand that he moved in his fingers constantly. He called out short advertising jingles and words as we continued from station to station. When the man and the boy got up from their seats to exit, the boy turned and leaned down and curled his hand over the fabric of the seat and scratched where he had been sitting. He then opened his hand flat and rubbed it over the vertical aluminum and glass partition bordering the seat.

The latest theory of brain science has a lot to say about how this boy was experiencing his environment. The brain is a “predictive engine that builds our conscious experience for us. We’re not seeing what we see. We’re predicting what we should see.” says philosopher of cognition Mark Miller. His mentor, philosopher Andy Clark looks at neural differences in the context of the theory of Predictive Processing in an engaging presentation —How the Brain Shapes Reality. Both Clark and Miller are updating the idea that our cognition is outside-in, the world comes in through our senses and we react accordingly. Predictive Processing is the complete opposite, the majority of the work of perceiving the world is inside-out.

The theory helps to explain the inner workings of the brain where top down internal neural activity far outnumbers the sensory information coming in. Returning to the boy on the train, Clark suggested that in some atypical neural brains the sensory data is more overwhelming. The boys use of sound, fine motor skills, and his tactile connection to space may be his way of making the world cohere to him. If our brain is predictive, what happens when we have prediction errors? This is what all the neural activity is about—error correction, prediction errors help us to remodel our predictions to perceive the world better—-but there can be sticks tossed into the spokes of this spinning wheel. Clark describes how in autism the incoming sensory evidence generates waves of prediction error that make the world seem full of important yet unexplained details and hence very hard to master.

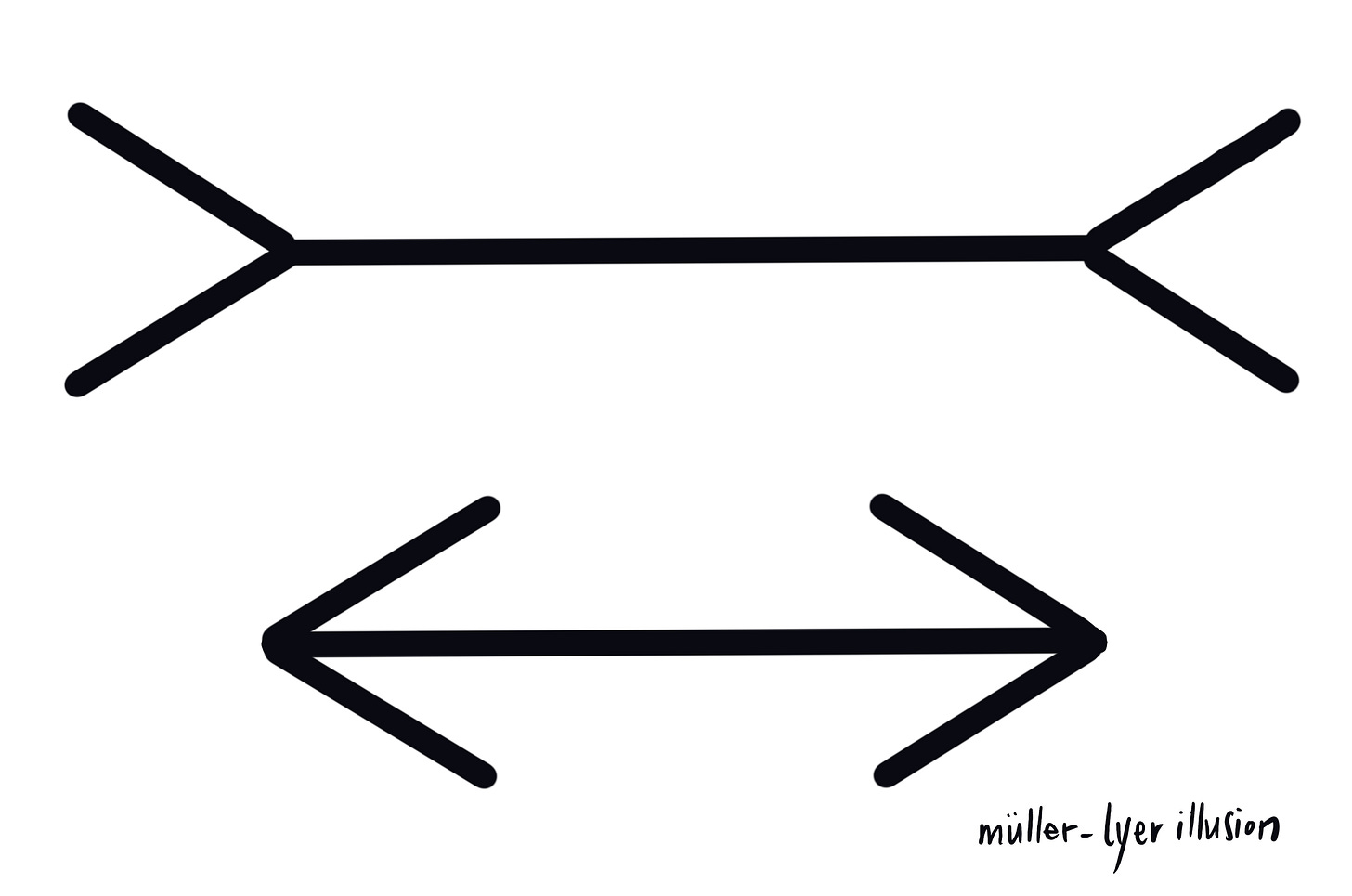

Mark Miller sees our brain as an optimal engine, trying to find the optimal way to create our reality. He has an interesting discussion on the Gray Area podcast with Oshan Jarow, a staff writer at Vox. Miller describes Predictive Processing as the pre-eminent theory in brain science today. It’s important to remember it is a theory and as he says, ‘we haven’t come to the end of science.’ One criticism of PP is embodied by the illusion above. The 2 straight lines are the same length, we can’t perceive that. If our brains are error correcting and updating our models of the world—-why are we not perceiving this? We can talk all we want about visual context and how depth is perceived, but it’s good to know that there are still parts of our perception that have a mind of their own.

Clark has a response about the line length illusion…precision-weighting. There’s a lot going on in our heads it seems. Not only are we predicting, dealing with prediction errors, we are also judging the reliability of the sensory predictions. In the paper, Predictive Processing and Some Disillusions about Illusions, authors Shaun Gallagher, Daniel Hutto & Inês Hipólito share Clark’s explanation for illusions fooling our perception …“ the weight given to sensory prediction error is varied according to how reliable (how noisy, certain, or uncertain) the signal is taken to be…flexible precision-weighting allows for an "astonishingly fluid and context-responsive system.” Gallagher et al aren’t buying it, the communication flow containing the illusion is stopped, we aren’t error correcting—that’s beyond flexible and fluid. The predictive picture inside our heads is still not fully in focus.

Predictive processing is described by Miller as a prediction system that needs to be provoked with uncertainty. I believe there is a critical role for art in this system and an ideal place to help build your grip on reality—-the drawing pad. The first exercise in drawing begins with not drawing, but thinking about how you think about drawing. I’m not trying to be meta here (it’s hard enough navigating all these cognitive philosopher’s ideas). I don’t teach how to draw but how to learn to draw. The best starting point is looking for the frames we use, or the models we have constructed to perceive our world and guide our hand.

Taking on a practice that offers endless opportunities for uncertainty, as Miller says, “the right amount of chaos” helps us to build resilience and tap into the resources necessary to manage uncertainty well. Drawing, because it involves attention, visual perception, and the sensory motor skills of the body is a complete cognitive exercise machine. You hit a wall in your drawing, do another where you get a win, return to the task with more reserves. This is error correction and updating your connection to reality with just paper and a drawing tool.

Cognitive science likens the brain architecture to the towers and wires and conduits that make up our vast network of communication technology, but the construct of this comprehensive system offers us no insight into the conversations and emotions traded across these wires. Predictive Processing is an incredible look into the dark room of our brains, lighting our neuronal pathways but we are still stumbling in the gloom with the content, the soul in the machine.