Solving the most complex problems we have in this world may begin with a box of crayons. My partner, Lorraine Tuson had a question for her students, how many of you drew with crayons as a child and do you see a generation in the future that won’t have this experience? We teach in an Illustration program, so the students likely skew towards adults that drew as kids. Maybe more questions to ask are what did you draw and what did you draw from?

My early drawing practice influenced by Spider-Man and Mad Magazine and then later photographic reference was balanced by a great high school art teacher B.J. Levac. She forced us to draw from observation and to draw each other as there was no way we would have life models in our Catholic High School back then. The first time I drew a life model was my first drawing class in College. I don’t find it strange that drawing from observation is more and more rare. We have disconnected our seeing of the world from the real, but taking the next step of removing our grip on the world by not engaging with materials, is a step into the abyss.

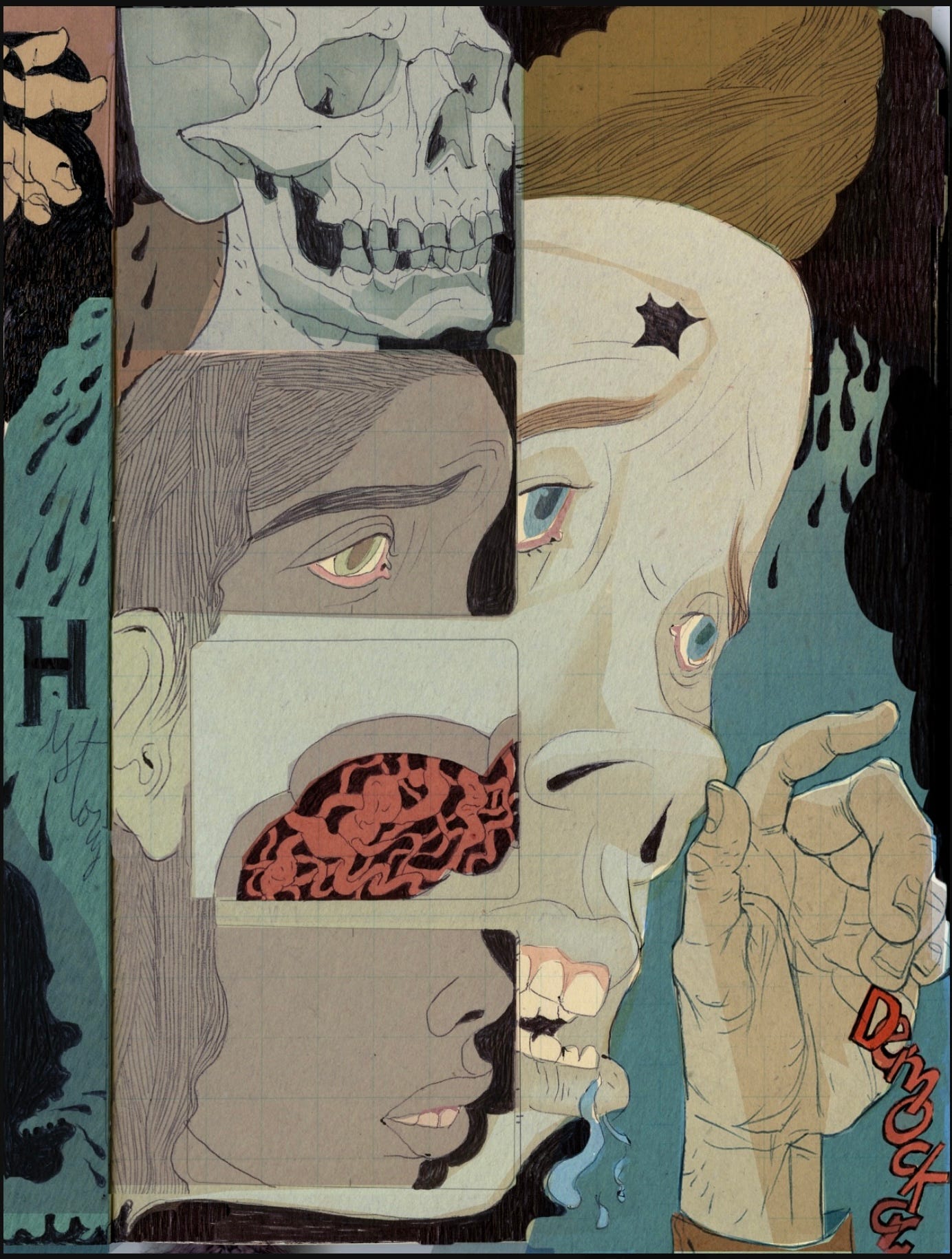

We are experiencing the cost of our visual distraction as our collective culture is incentivized to capture our attention and focus, in an endless loop of meaninglessness. I think there is an origin point that gave this visual maelstrom purchase in our cognition, a door we let swing open and this thing rushed in. Our loss of holding onto the real, the actual interface of hands-on engagement with the texture and fabric of this world when we were kids. Yup, the crayons again.

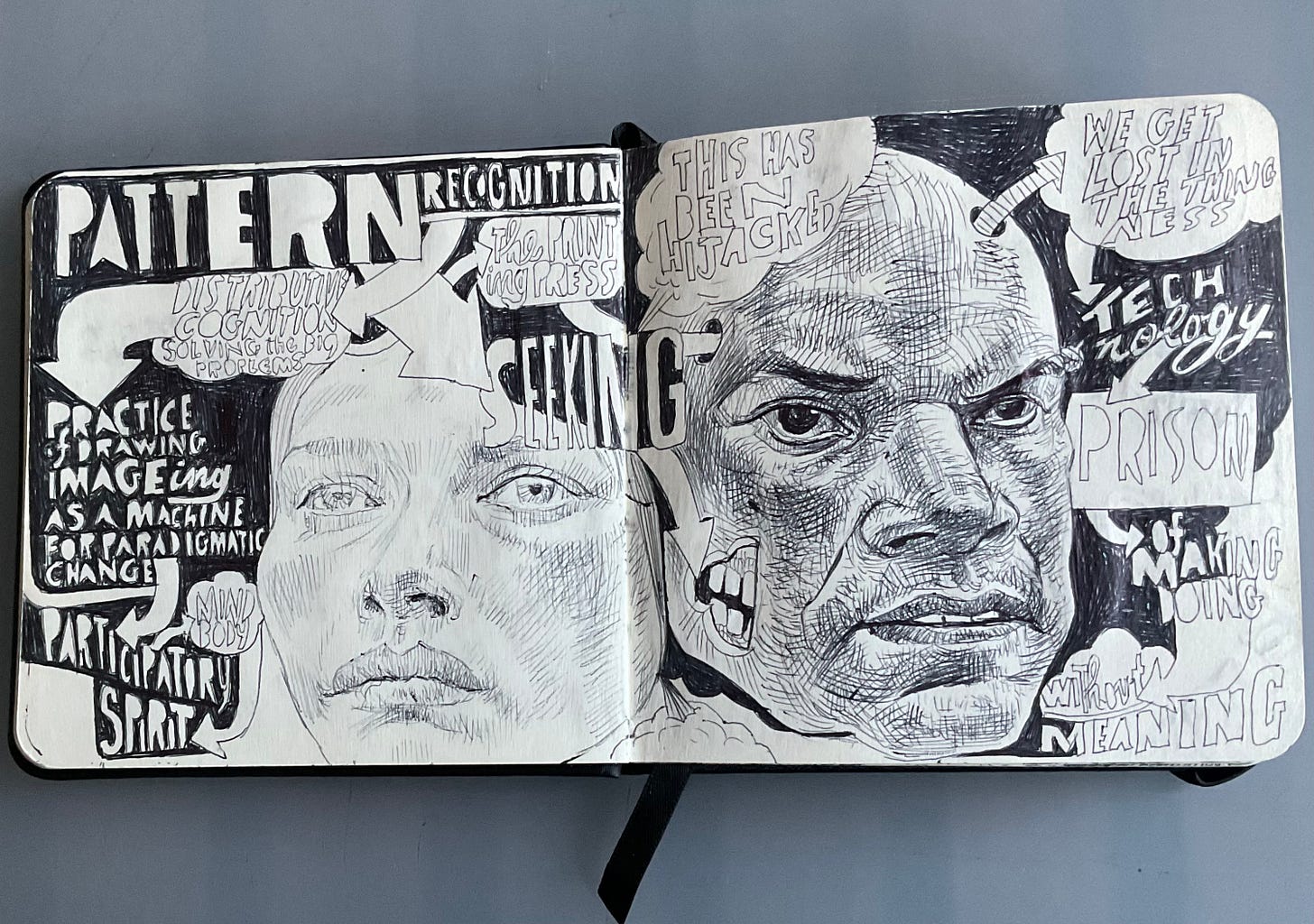

There is a cost to not engaging our hands in the work of shaping the materials around us. The poke, tap, and swipe of screens don’t open new experiences, just apps— and close off the most important lessons our bodies and minds need—how we grip this world. I think the costs start when we loosen that grip and tear our fingers from the slow plodding of learning to manipulate letters, words, and numbers and topple into the pixels and splendour of noise and spectacle parading brightly across the screen.

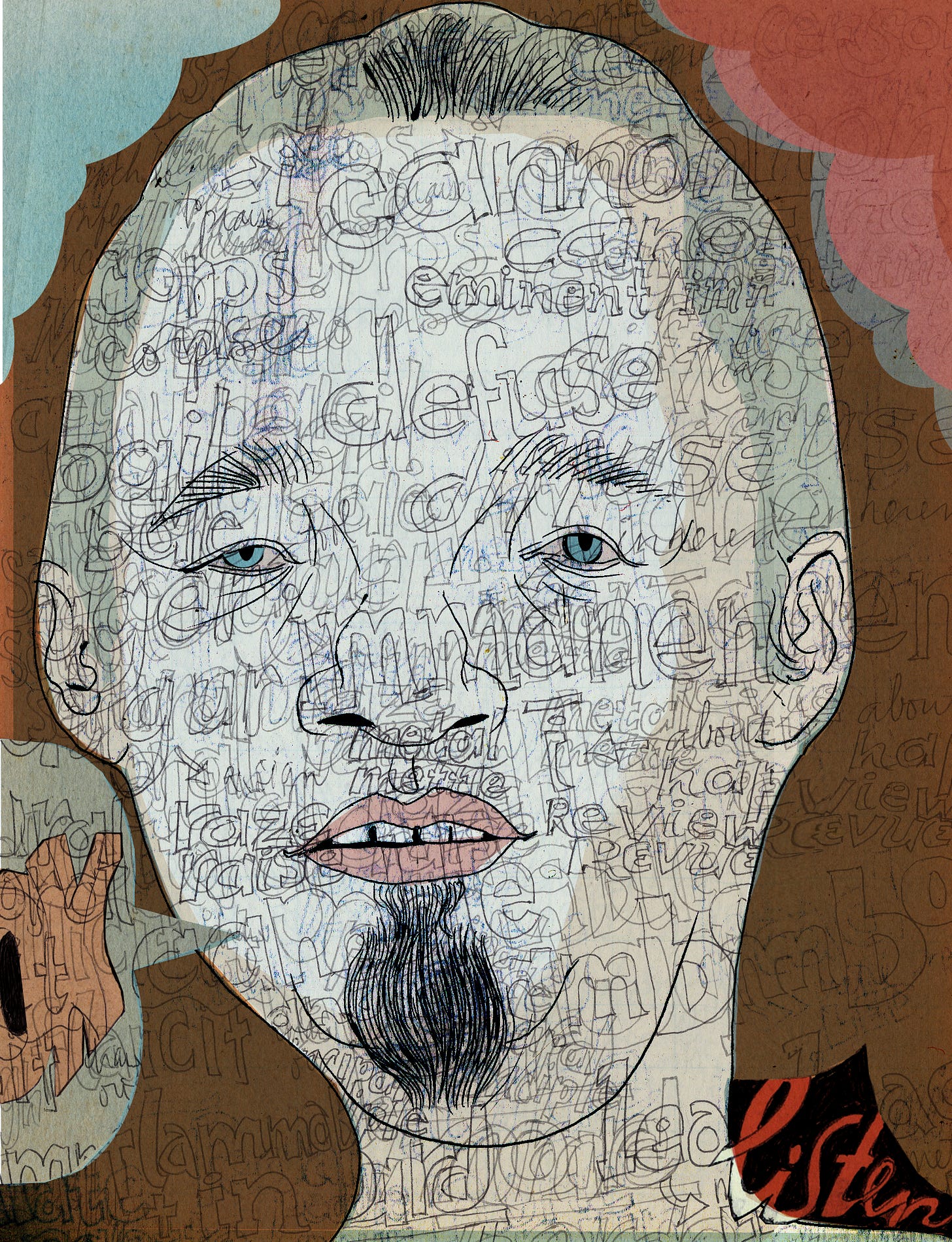

This is the actual beating heart of A.I.—-how could we not reach for that pulsing, alive thing casting its garish light on our sad blank pages and pencils. There is no contest. We know a loser when we see one—-and that’s the most perverse aspect of this whole project—-human as loser, as less than. Strip mine all the value out of human work, separate us from the embodied cognition that makes us unique and then feed us this pixel flavored gruel of our own creativity as if it is revelatory.

I’m going to fight back with my ballpoint pen firmly in my hand, ok, not now—I’m typing, but I know in drawing there is a dialogue with my hand, head, and the subject, that no A.I. can simulate—-because it is about caring and opening a space for other people to express their thinking and viewpoint. We learn to embrace the language of drawing through the act of making—not handheld, handmade. We are not sitting at the trough being fed from the hive mind, we are making our own world and paying attention to our thoughts, our hand and the drawing. Bring on the crayons.

Had my first experience being (potentially) hired to paint over AI images. Impossible to hide my disappointment over zoom. More gigs in the last 6 months have been moral quandaries than in whole career.