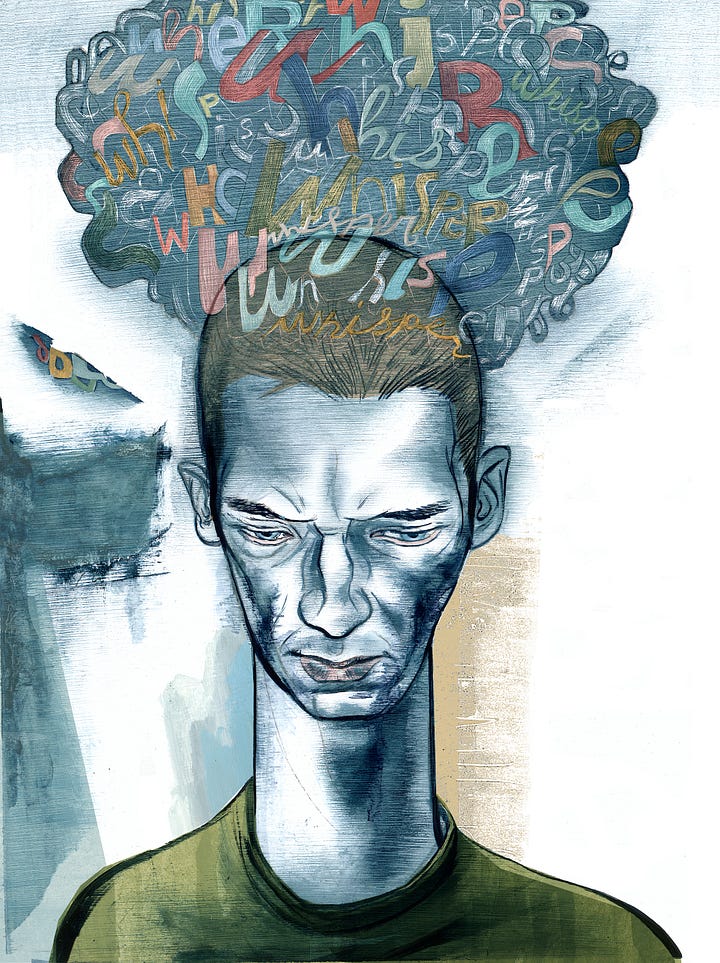

Some great conversations this week with Artists, Illustrators, Art Directors and Animators about our collective futures as A.I. looms larger. My Associate Dean at Sheridan, Myles Bartlett described A.I. “as an existential crisis for educators, artificial intelligence represents a knowledge revolution where the Internet represented an information revolution.” Maybe there is some good news in how we define knowledge in relationship to A.I..

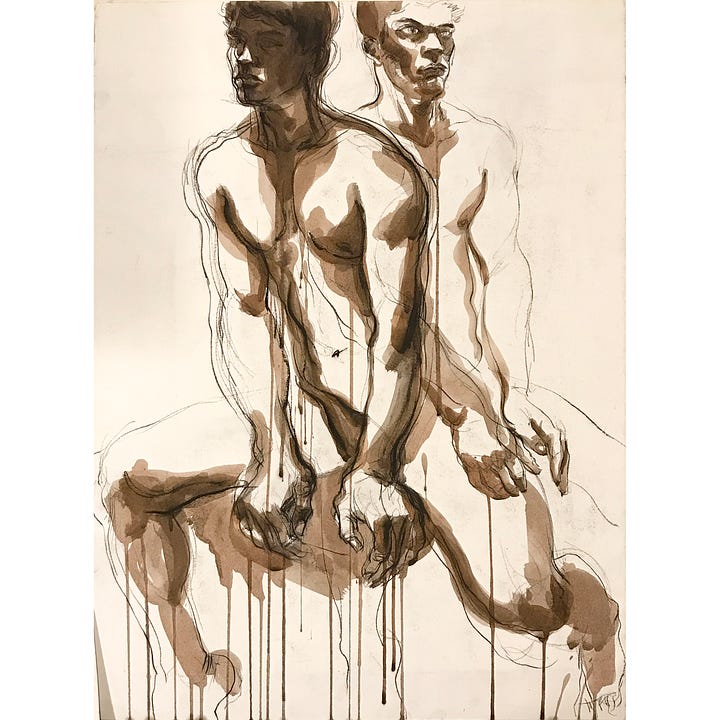

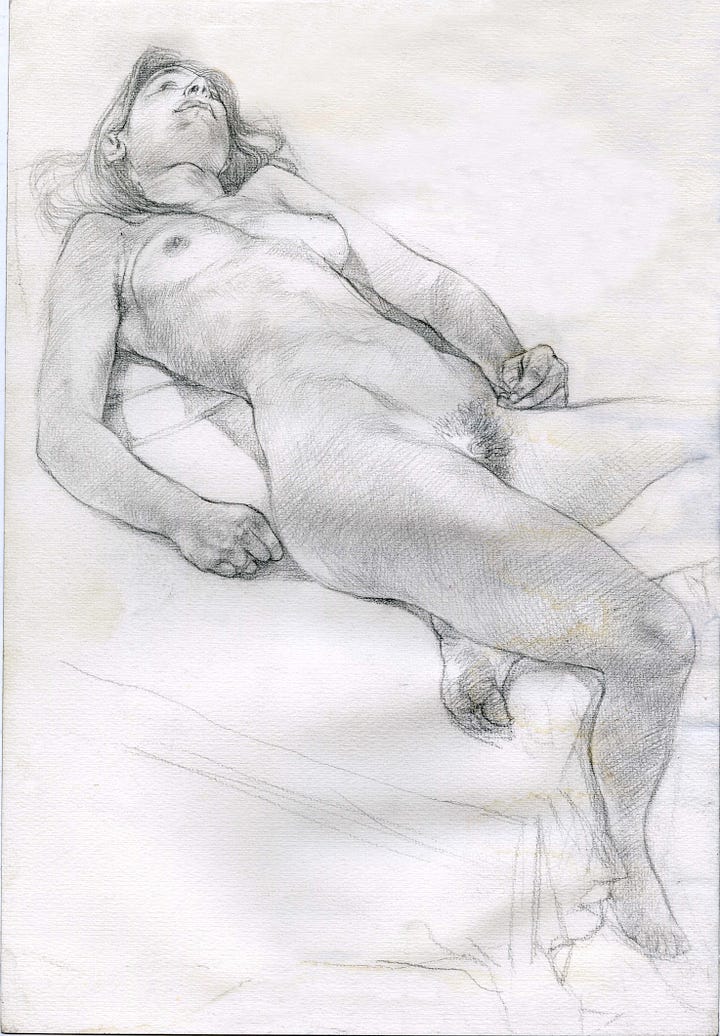

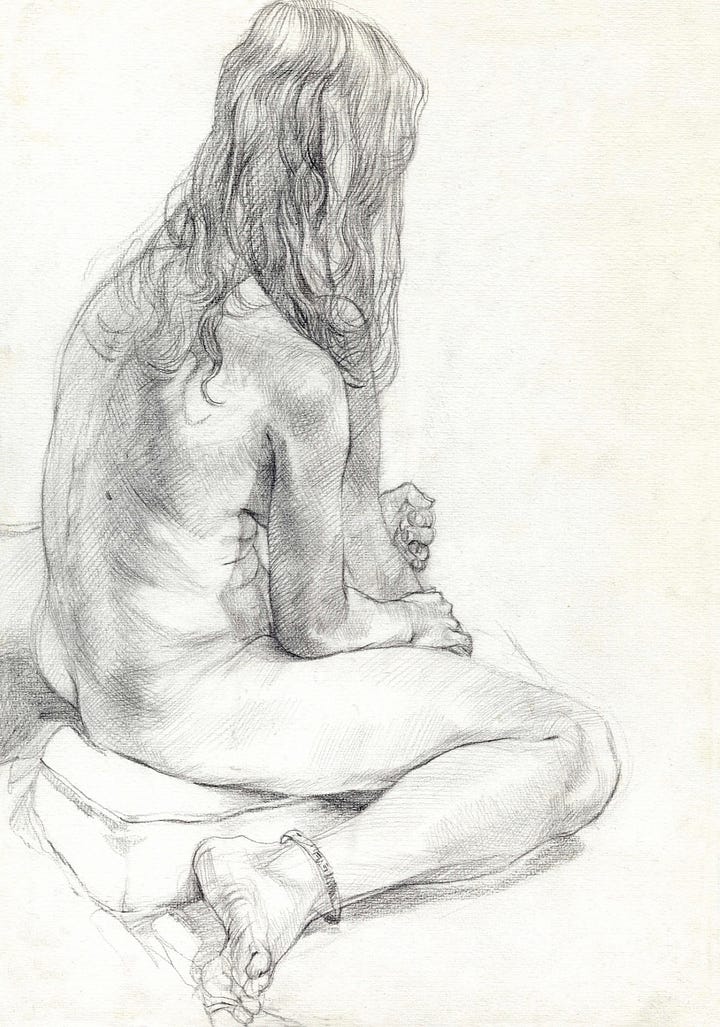

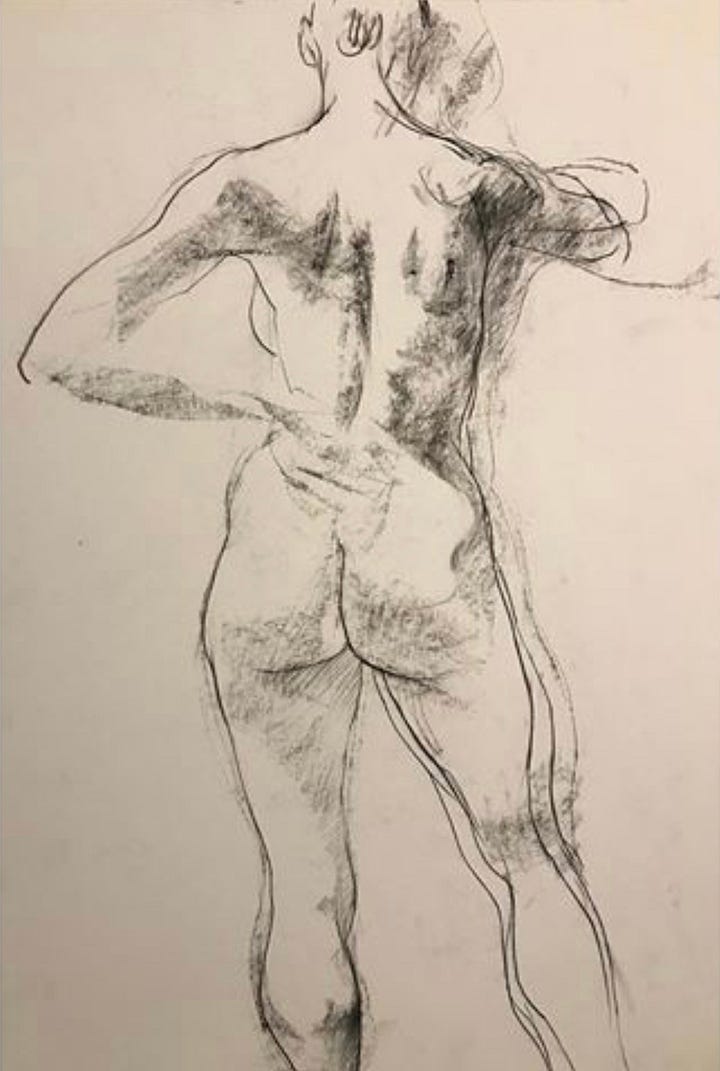

Exhibit A will be Drawing from Life. I situate this drawing practice as a central activity whose primacy is only made more urgent by A.I. tools. We have incredible cognitive bandwidth dedicated to our eyes, hands, and senses. We haven’t evolved out of our bodies and knowledge is more than the sum of our collected hits scraped into transformers. The shared energy of drawing another person is an incredible experience of active presence and participatory knowing.

University of Toronto Cognitive Scientist John Vervaeke provides an excellent overview on the 4 types of knowing. The first 2–- propositional and procedural knowing are central to the LLMs. Propositional knowledge is information, facts, the rules, so much of the knowing about things and the TRUTH that we see A.I. as ‘expert’ in. The next knowing procedural, is knowing how to do things—-moving theory to practice and building skills to achieve expertise. The generative A.I.’s seem to be developing new skills everyday.

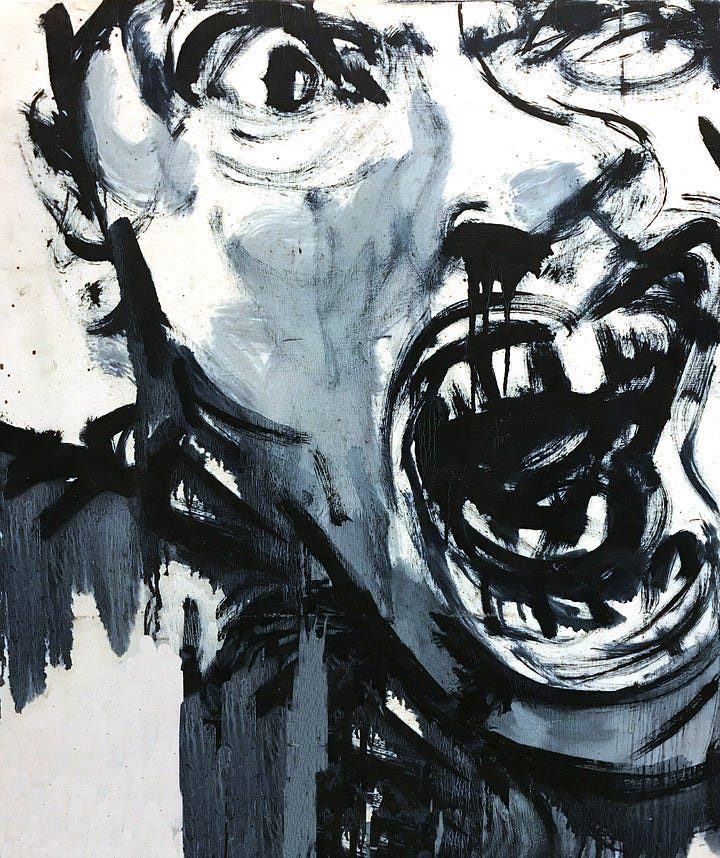

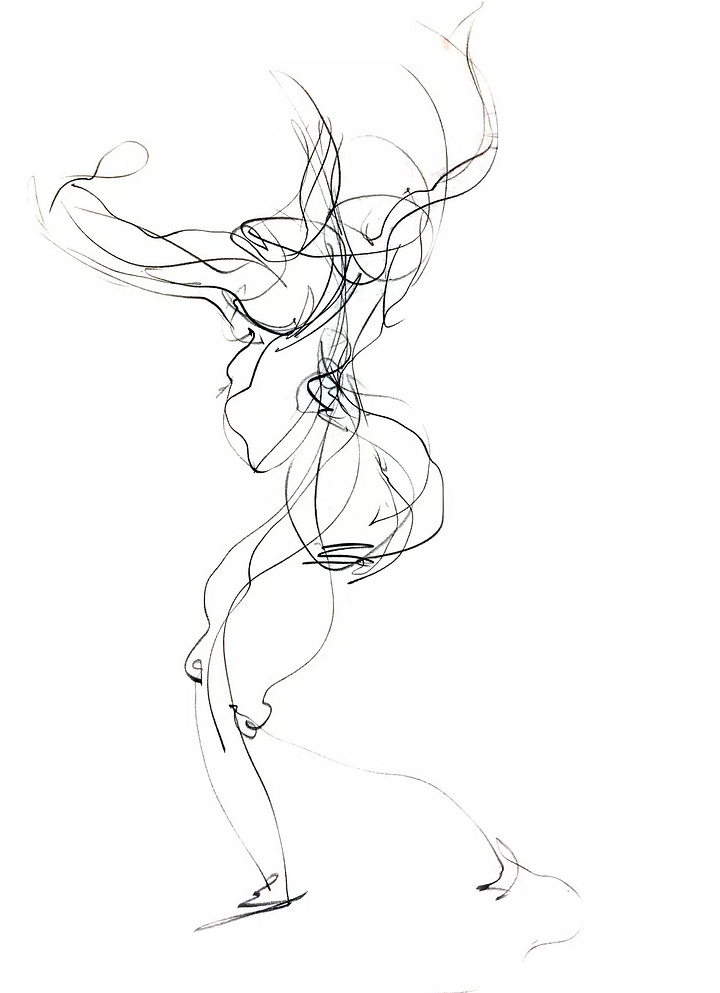

The next 2, perspectival and participatory knowing are likely where us humans may stage our last stand. This is where the drawing studio can provide a battleground. Perspectival knowledge is perceiving the world from our perspective, it’s dynamic and situational knowing—-being present and being aware of our limits and the value of other perspectives to be able to fit together our knowledge. Participatory knowledge is a connection to being, embedded and embodied in a nowness that allows for improvisation and complexity of knowing without thinking.

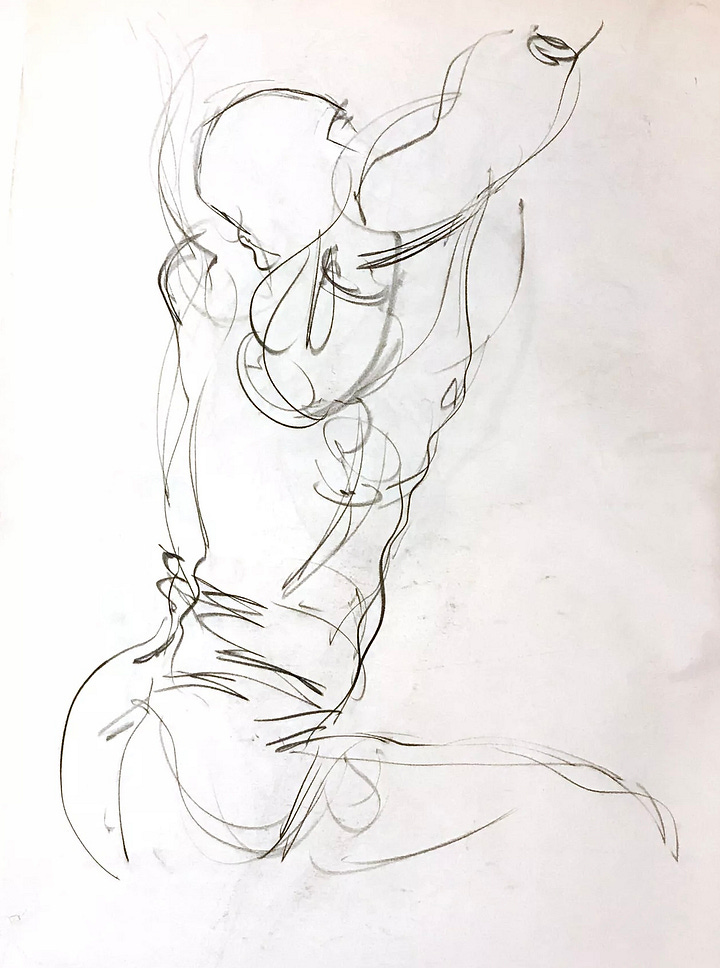

Go to YouTube to see drawing practice that circles like hungry buzzards around propositional and procedural knowledge. The reliance on mastery, plaster casts, and ‘historical’ methods and techniques in aid of capturing certainty has countless adherents. But this is grabbing the drawing tool from the wrong end. Drawing survives today despite this dangerous territory, of performance anxiety, bad habits, and even worse ideas shared in countless YouTube videos. If done right, it offers an incredible wealth of failure and mistakes that lead to the insight that what is right is wrong and what is easy is hard.

“Constructing meaning rather than receiving information. Art must defend the uncertain” William Kentridge

When we see the creative process as a thing, an act, an object, a technique, it becomes easy to believe we can prompt its products into existence. But making art is a set of circumstances and collisions that are set in motion by unlikely vehicles. The slow building up of form, waiting for ink to dry, the humidity of the air and the breathing and heart beating of another person as their body sinks deeper into the pose. Drawing interrogates it’s subject.

So reach for your pencil, pen, or brush and turn to a fresh page and make a mark that leads you in defiance of certainty and a finished product. The great American artist Robert Rauschenberg’s advice is perfect here, “ Stop remembering something that you are sure of everyday to make space for the new mistakes.”