I wasn’t looking for this book. I was in a bookstore and looking at books on German painting. I also love typography and the cover with its illustrated subject pulled me in. At first, paging through the book I thought it was the record of AEG and it’s evolution through every realm of media, product, and building——then I noticed that it was actually about a seven year experiment—-the collaboration between an artist, Peter Behrens and a large industrial company. Behrens lived at a time of profound change, the beginning of the 20th century, with a world order crashing into technology—-with ideas and personalities battling about art, mechanization, design, engineering, and architecture.

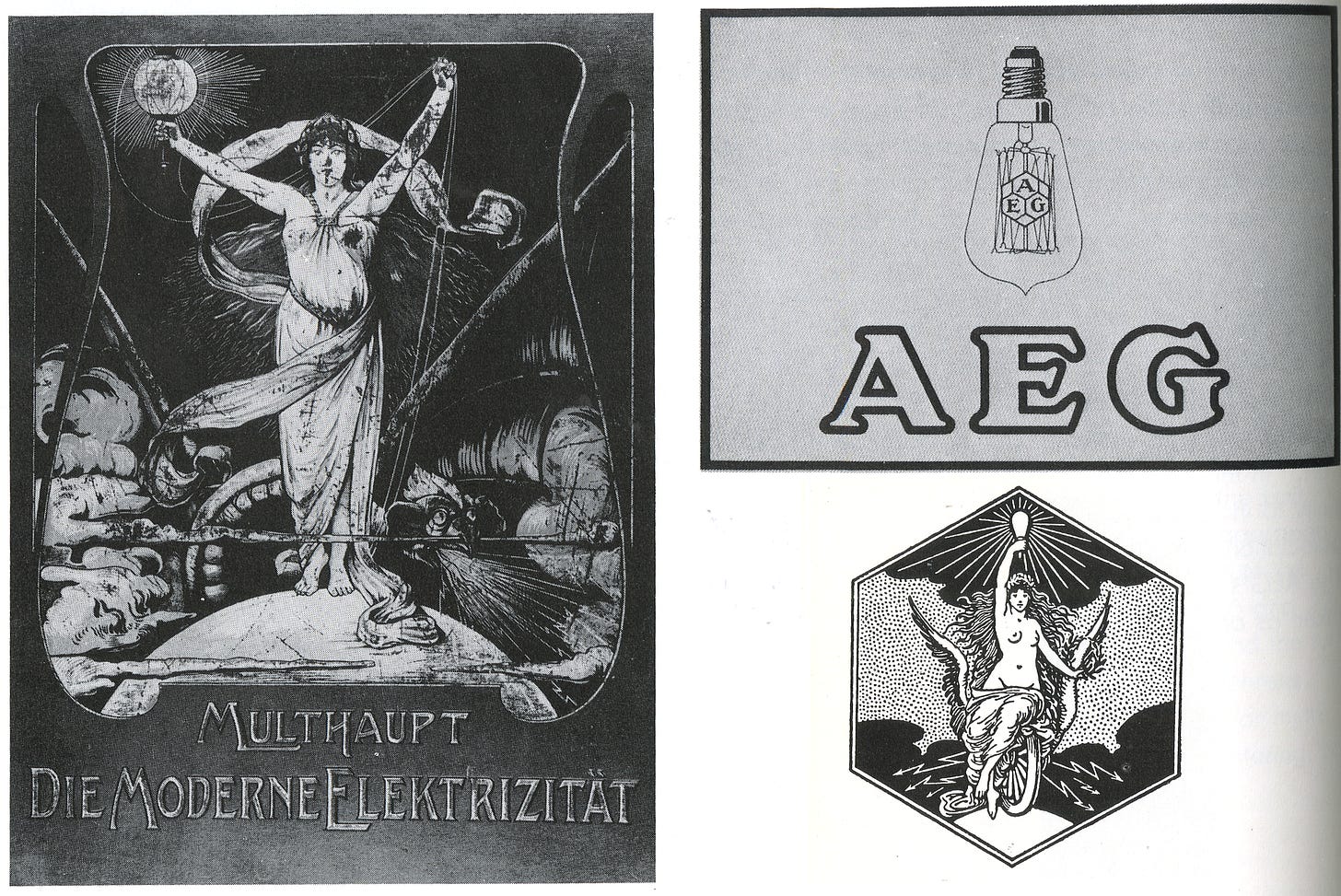

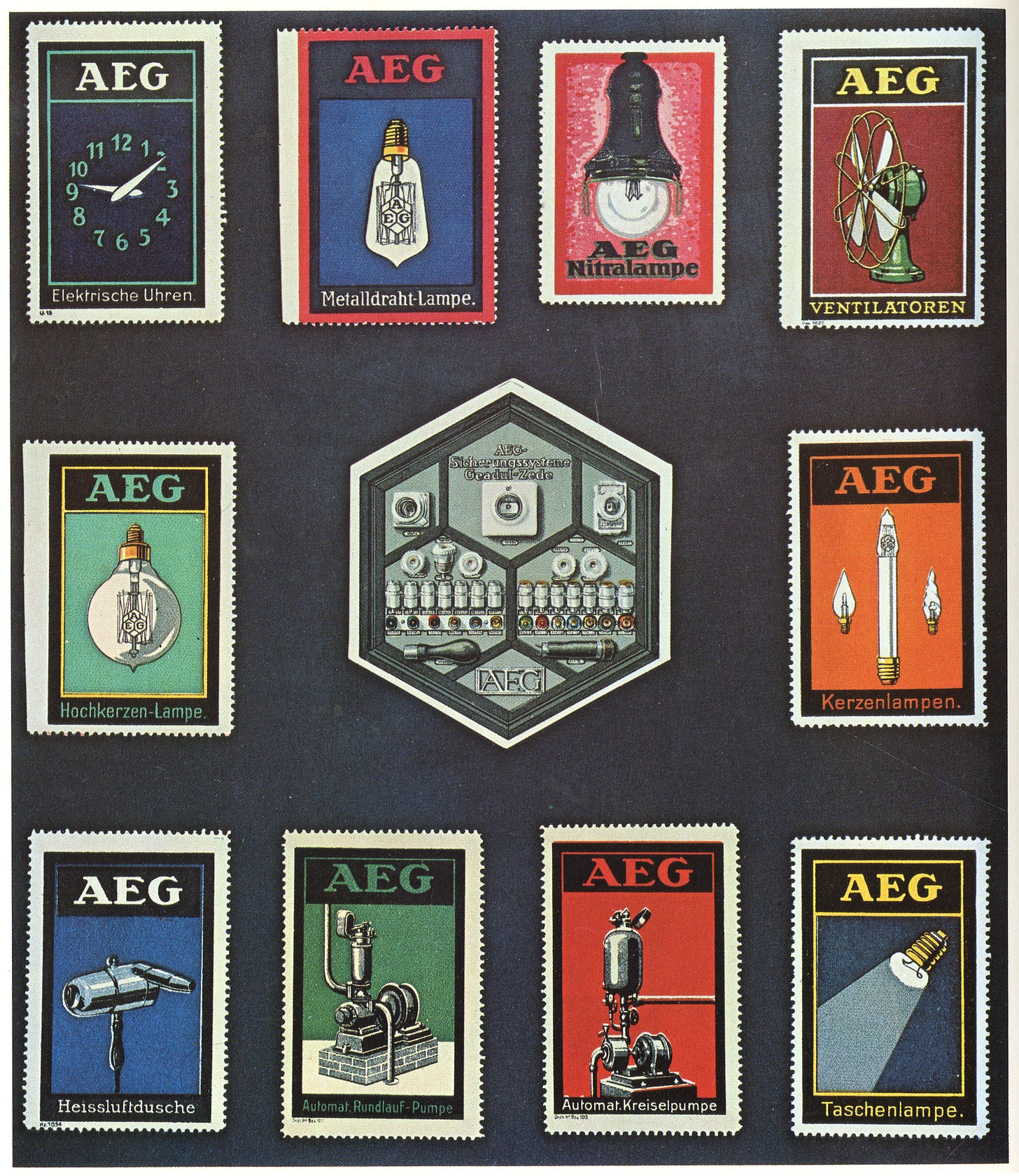

Peter Behrens was a German architect, graphic artist and industrial designer. He began as a painter and illustrator. In 1907, Behrens and 10 others including a dozen companies founded the German Werkbund. The entire project was to improve the level of taste in the design of everyday products. Behrens designed everything from typefaces, products, offices, factories and worker’s homes. His work in 1907 for the AEG (Allgemeine Elektricitäts Gesellschaft was founded in 1883 and produced electrical equipment and appliances as well as constructed 248 powers stations that brought lighting across Germany) ‘reorganized everything visual’, as he designed the corporate identity, including product design, publicity, and buildings. Behrens worked for a company that provided light and the latest technology to Germany, but like many industrial companies of the early 20th century they associated their industrial mission with a classical or mythological symbol—-the brand images of the Goddess of Light.

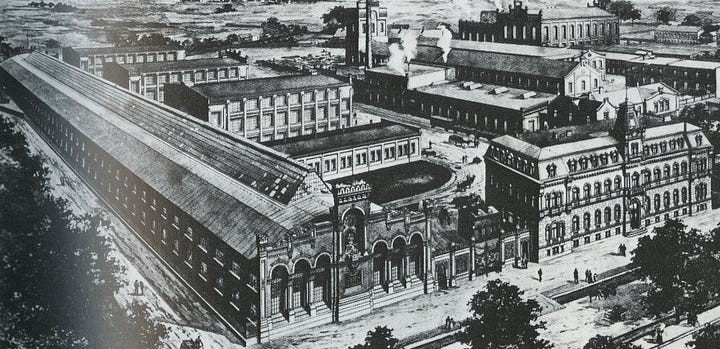

Behrens did have a mission, but his was not a new religion of the machine, the short distance from the handmade and the oil lamp to the light bulb, likely offered him a more humanistic perspective. He saw the applied arts like a public utility, a well of forms informed by the function of machine production. He was a modernist, and his work renounced the imitation of handcrafted work, materials, and historical styles. A clear example of the ideas at the heart of Behren’s modernism—-beyond ‘form follows function’, is comparing 2 AEG factories, Behrens Turbine Hall, and the Riga factory, built 5 years earlier. The Riga factory had an elaborate decorative facade and banks of small windows. It’s a false front and is hiding the fact of its function, the streetscape can’t be sullied by a factory. One of Behrens first concerns was how did the building support the work and the workers. The Riga building did neither. Behren’s Turbine Hall has no unnecessary fake facade, the building form supports the needs of the work done and the massive windows flood the work space with natural light. It is functional, but has a monumental beauty, utilizing balanced proportions and forms and celebrates the industry of its purpose. The Behrens led AEG work of 1907-1914 was a unique experiment in art and industry. It was not without controversy or strong opposition at the time, equally despised by artists—-Behrens as a traitor, and industrialists —keep the artists hands off of our dials and gauges. I think in some way we share the Marxist social theorist Leo Kofler’s view of large industrial factories as, “civilization perverted into an inhuman process.” I’m not arguing for a re-assessment of the assembly line, I’m looking for threads we can pick up in our own shifting economic environment.

Behrens understood craft and tradition, but he also strove for a graceful beauty in applied art and a utility of design to streamline production. Here is Tilmann Buddensieg describing Behrens kettle design,”…a smooth, rivet free, streamlined form…As if with hedge-trimming shears, Behrens cutoff the ornate forms of the original in order to create…variation on the theme of an electric kettle.” He designed 3 shapes, in 3 materials, in 3 finishes, and in 3 sizes. The profound change of the hand made to the mass produced was an incredible disruption at the turn of the 20th century. Behrens was aware of the poorly designed mass made product, he was able to design a product that met both production efficiency and an aesthetic approach to elevate the design quality of the mass produced. He also made products whose cost was within the means of working people. He was only able to do that because as Ian Boyd Whyte writes in Industriekultur, “ he ennobled the industrial process via the means at an artist’s disposal, such as scale, sequence, proportion, rhythm, light, shade, and the play of materials.” Behrens saw a critical role for the artist to play in the research process, to problem solve and to provide value in every aspect of the companies products. He believed that design could impact culture.

The lasting legacy of Behrens will prove to be his influence on 3 young architects that worked as assistants in his studio. These architectural titans of the 20th century all worked for Behrens. As his architectural practice grew he took on more assistants which included, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier, and Walter Gropius.

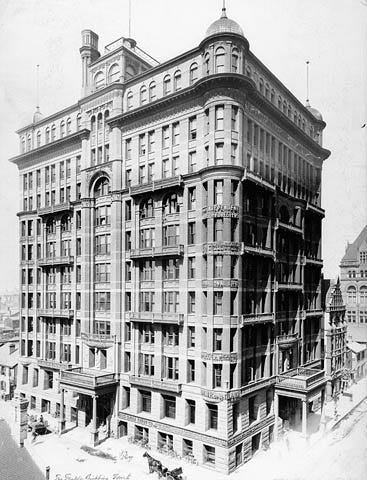

Ok, I hate name dropping—-but these 3! I live in Toronto and can experience the real deal Mies architecture in the black towers of the TD Centre, built in 1967–the plaza inside the towers is the best of what modernist architecture could be. The point of the building is that the exposed black girders are the supports of the building, not a decorative cladding. I visited his Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin in 2022, another awe inspiring architectural design. Corbusier is the cold heart of modernism taken too far as in his maxim—-“A house is a machine for living in.” Gropius founded the Bauhaus and his ideas about art, design, prototyping, and industrial production informs all applied art practices. What lessons or mistakes can we learn from these first responders to the art/industry collision?

Mistakes

Modernism has much to answer for, especially the cookie cutter International style of architecture blighting urban centres. Toronto’s downtown had a rich history of architecture that was obliterated as the late 60’s and 70’s urban renewal focused on innovation, the automobile and the glass tower. There were a number of levers at play in these terrible design and planning decisions—-money, politics, and power come to mind. Worse we lost track of the human values that in 1907 guided Behrens in his design of buildings and streetscapes.

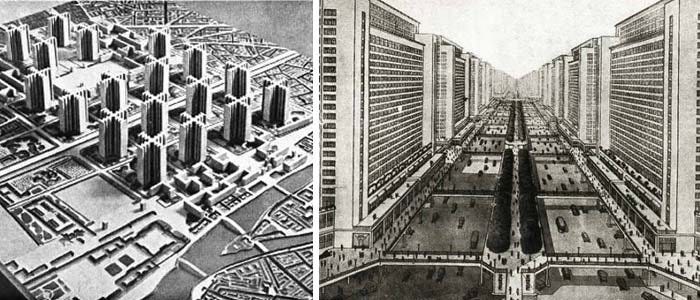

Corbusier crimes include brutish uniformity, city planning for the convenience of the automobile, the razing of neighborhoods to create repetitive unlivable housing blocks, and the creation of the car centred suburbs.

He can’t be redeemed, but partly forgiven by the incredible Chapelle Notre-Dame du Haut in Ronchamp France, a Catholic chapel built in 1954.

Lessons

Gropius had a powerful mission for the Bauhaus, an art school that combined craft and fine art in a new applied art of design for mass production, that was no doubt sourced in Behrens studio, “to liberate the creative artists from otherworldliness and reintegrate them into the workaday world of realities and at the same time to broaden and humanize the rigid, almost material mind of the business person.” The key here is that the artist as designer was not removed from the process but is central to it. The focus on design and the value of a design aesthetic has likely been a critical factor in Apple being valued as the world’s richest company. You can see some of Apple’s approach to their design in Behrens thoughts on product design as,

"a worthy expression of the working methods," to find external forms that would "no longer hint at the complication of the technical organism, "and thus to conquer the world of mechanization with the power of artistic form and aesthetic order.

So here we are today, Künstlicheintelligenzkultur (A.I. culture) and what can we learn from the Behrens studio and the uneasy marriage of art and industry? The legacy of the studio and its influence strayed from the original ideas developed in 1907, because the ideas had to go out into the world and become real. Maybe we can borrow from the artist’s focus on design and actual materials and avoid the industrialists certainty that technology is about important ideas because new products are being made. Novelty may satisfy an appetite but doesn’t feed us.

Peter Behren’s work in all areas was beautiful because the machine didn’t determine the object, he still had his hands on the design process. His larger project of effecting taste and the transformative power of design was derailed by World War 1, but maybe the rise of Apple has some of Behrens DNA in it. Think different was not just Apple’s advertising slogan it was a call to see mechanization or technology as not an end in itself, it is not an answer, or a destination, but a tool that needs to be wielded by people, and not yoking us to it. Do they still believe that?

In Corbusier’s ideas we can see the fetishization of rational order and function unfettered by the utility of the production process that gave Behrens and Gropius purpose. Corbusier removed people from the machine of his designs and created ideas that people were supposed to be inserted into, like tiles snapped into a design. This is the emptiness of a technology that removes the human from the design/making equation which animates a machine/system’s process. We lose access to the skills and thinking necessary to build our own ideas, and ultimately we are disconnected from the expression of our inner life.

Ah yes. Living in a house designed by an architect “with vision!” Very complicated. lol.

Nice piece Joe. Le Corbusier though worth a second look. Prolific painter. Many of his floor plans inspired by abstract painting compositions. See La Tourette and many residential projects