I made a vow when I started teaching that I wouldn’t do what many of my College teachers did…try to close another person’s mind. I was lucky that I travelled right after College and the thin stretched theories and bad ideas didn’t survive real experience in Europe. I was taught to fear and despise contemporary art and abstraction and boy did my Profs hate Picasso’s work, the man himself they were mute on, but the work, they despised everything about it.

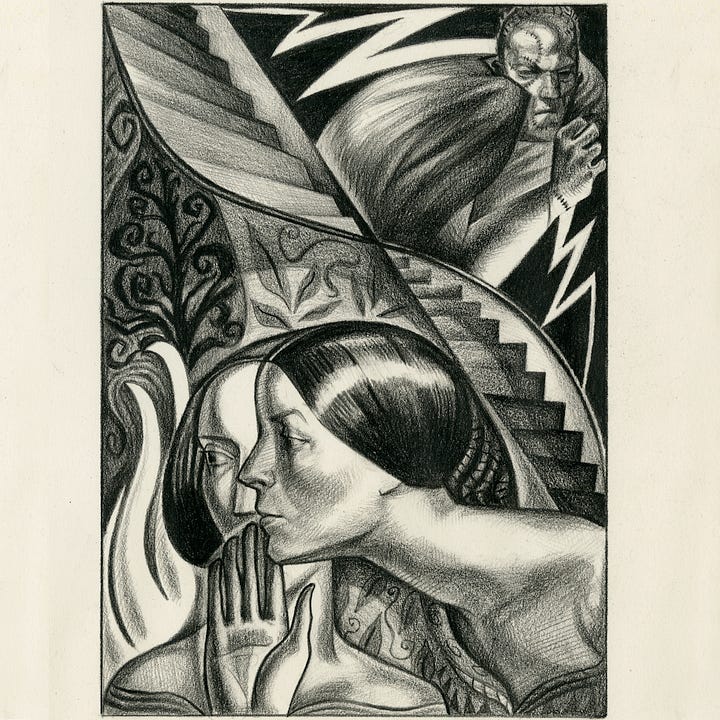

Picasso was my gateway drug to contemporary art, everything changed after the Museu Picasso in Barcelona. I made my way North through Europe and washed the last vestiges of my education’s prejudice from my eyes as I walked through the galleries and grounds of the Louisiana Museum outside Copenhagen. I made some terrible artwork when I returned from Europe and I even avoided the figure for over a year, as if that was the problem—-likely soaking in other bad ideas—gee thanks semiotics and postmodernism.

Teaching saved me. It was right time, right place. My personal life radically changed, war was happening in the Gulf, 24 hour TV news started, and I was working on the total visual overhaul of the Globe and Mail newspaper. Events, ideas, and images were vividly urgent and real. Teaching became another opportunity to expand my ideas and the centring of visual communication and meaning. It also helped with a necessary expansion in my approach to ideas. The act of teaching needed to be fueled by exploration.

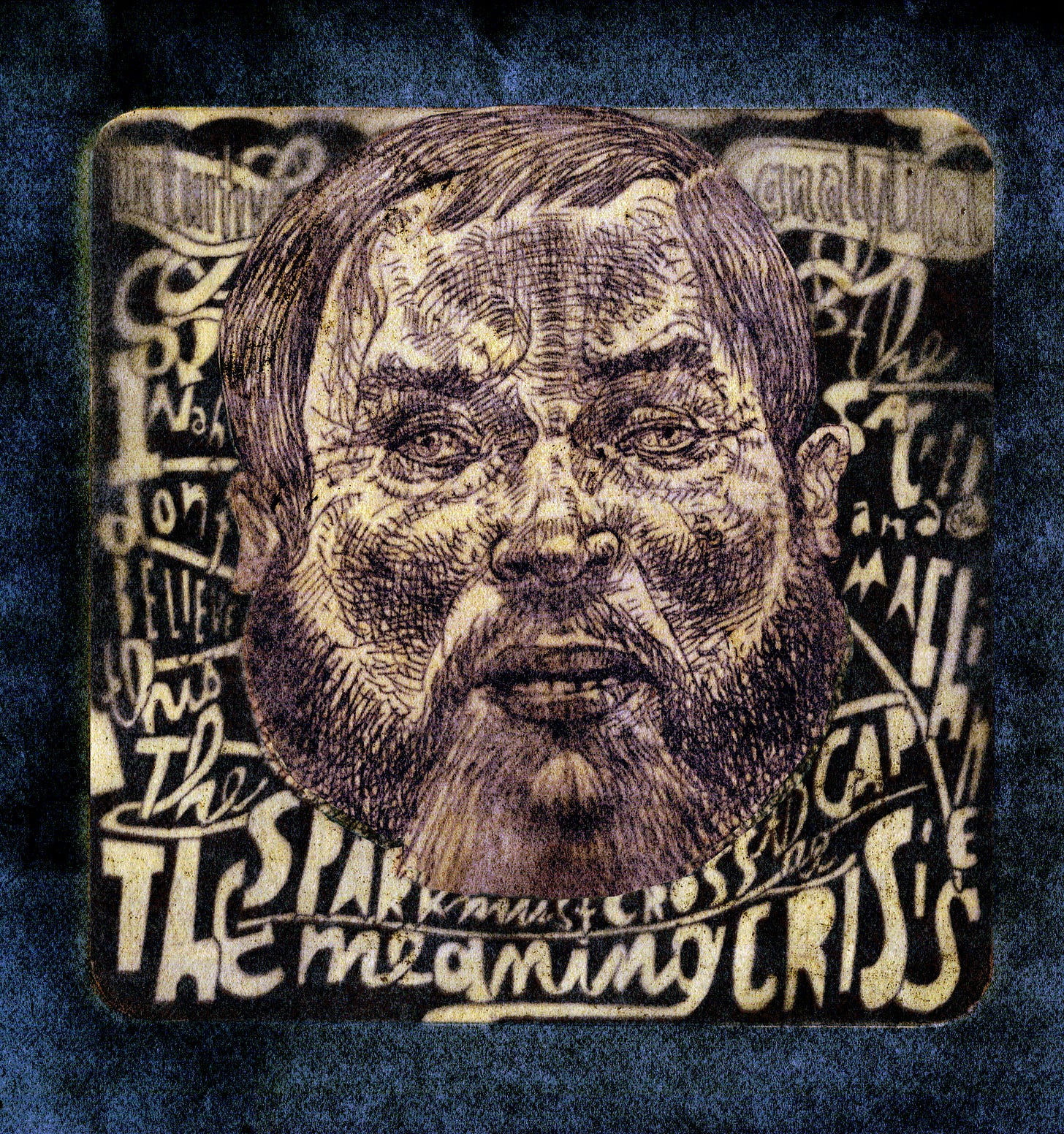

The world has changed profoundly in the 34 years since I first walked into a drawing studio to teach drawing. What hasn’t changed is the urgency and need for images to express and explore ideas. The difficulty is the soil in which those ideas can take root is sparse. At the heart of creative problem solving is finding connections between disparate ideas and following random threads in and out of dark alleys. The vast access to information that is afforded us today is frictionless, fast, and circumscribed. Poor soil to plant seeds. Does it need to be that way?

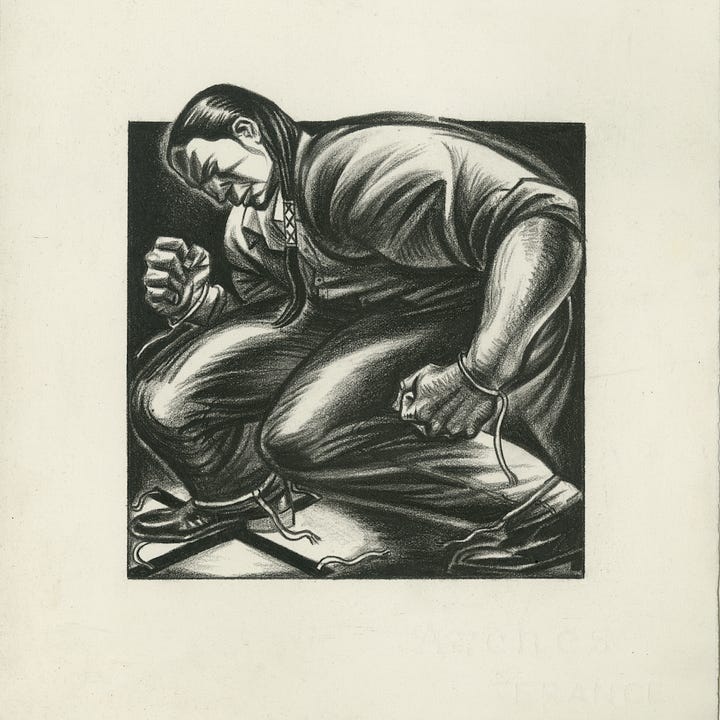

On the book shelf across from me I have books on Paul Rand, José Guadalupe Posada, John Heartfield, Pieter Bruegel, and Robert Rauschenberg. I can see the lines drawn between these different artists and my own practice, but the road I had to travel was circuitous and not always clearly marked. How do we expect students to develop curiosity based on research when they are on an information super highway with no detours at any point. I am not claiming any special powers, or the nostalgia of the good old days. There is much to laud in our access to information but we created a system that valued the wrong thing. The process of the search is what develops our thinking, not the answer. Our search engines have streamlined the experience of discovery like a well greased water slide, when we should be challenged to look farther and question more. Friction is necessary to create movement. Search engines should be centred on searching for nuance, but they are optimized to sell and to reduce complexity.

Art can now be reduced to a prompt, a series of questions that a nostalgia machine aggregates into a simulacrum of a picture. The ultimate product without process. I think down to our cellular level we know this is wrong but like search and social media our entanglement is being bred into us. Who cares who owns Tik Tok, when the thing itself, despite the helpful chemistry teachers, wellness gurus, and entrepreneurs, is a medium designed for attention capture and frictionless consumption. Here I was worried about closing minds, when we have built a culture that incentivizes we never open them.